By Michelle Superle

I learned about Braille from books, appropriately enough—from the Little House series, my childhood favourites. There I was, cozy on my couch, while back in 1800s Dakota poor Mary was going blind. Her family worried that wouldn’t be able to earn a living. To me, the greatest tragedy was that Mary would never again enjoy her favourite stories unless somebody read them to her. Until she learned Braille, that is.

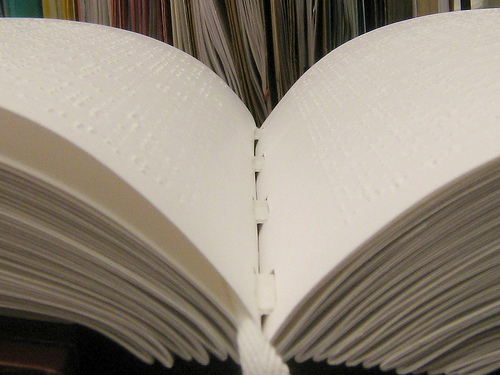

Photo Credit: ShellyS Flickr via Compfight cc

Photo Credit: ShellyS Flickr via Compfight cc

I was amazed. There was another way to read—a world of miniscule dots so small they eluded all but the most careful, persistent fingertips. And these mysterious dots had the power to open up the realm of story! As I read about Mary, I imagined losing my own sight. I wondered what it would feel like to lose stories as a result. I even tried to learn Braille for about five minutes, but it was too hard.

Mary was made of stronger stuff. She persisted. And because she was able to keep reading, she—like me—gained access to worlds full of places, people, and adventures she would never experience in reality. Imagine how small life would be without all those worlds we explore through reading. As a child, I couldn’t fathom something so awful. As a children’s lit prof today, I don’t want to.

Reading is considered a fundamental human right. It’s even enshrined in several articles of the UN Convention on the Rights of the Child. The UN Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities specifically recognizes the importance of Braille. How apt, then, there’s a special day dedicated to celebrating the six tiny dots that allow the blind independent access to information.

World Braille Day falls on January 4th –the birthday of Braille’s inventor. Louis Braille was a dedicated scholar whose blindness held back his studies. He created his ingenious system of dots to help the blind learn more successfully. The World Blind Union promotes this day to remind us that the independence Braille affords blind people is uniquely autonomous and cannot be replaced by technology like audiobooks and computer software.

I may have learned about Braille from a children’s story, but it was a book for grownups that recently reminded me of those dots’ power. In All the Light We Cannot See by Anthony Doerr, Braille functions as a touchstone for young Marie-Laure. Indeed, the ideas she gleans from reading shape her very identity. Her all-time favourite story is 20,000 Leagues Under the Sea, which not coincidentally emphasizes the novel’s central theme: life’s hidden undercurrents affect and connect us in powerful ways. By vicariously experiencing the twists of fate a blind French girl survives in World War II, readers are reminded of life’s mystery and fragility—not to mention the human spirit’s resilience.

Besides that, All the Light We Cannot See is masterfully written, offering velvety swathes of lyrical prose like this:

A metallic wintery light settles over the stables and vineyard and rifle range, and songbirds streak over the hills, great scattershot nets of passerines on their way south, a migratory throughway running right over the spires of the school. Once in a while a flock descends into one of the huge lindens on the grounds and seethes beneath its leaves.

The thought of anybody being deprived of such delicious language—and such an important, life affirming story—is unbearable.

World Braille Day reminds us that everyone has the right to access stories and information; it reminds us that with a little ingenuity (thanks Louis Braille!) and some persistence, everybody can.

Comments are closed.