Indigenizing the Academy — Making universities more welcoming for Aboriginal peoples

Indigenizing the Academy — Making universities more welcoming for Aboriginal peoples

For anyone new to academia, there’s a bit of confusion and trepidation.

Why do the professors wear those gowns at Convocation? How do you know when and where to apply for a scholarship? What’s a graduate degree?

For Aboriginal students, the gap between their worldview and mainstream academic culture can be even wider. Throw in decades of systemic racism within Canadian society; the devastating experience of many families with residential schools, foster care, and adoption outside of their communities; and the misrepresentation and stereotyping of Aboriginal people in the dominant historical narrative, and you have a lot of reasons for them to be wary of post-secondary education.

A growing number of universities and colleges are recognizing the need to make their campuses welcoming places for Aboriginal cultures, their knowledge and their learners. The formal name for the process is indigenization, and UFV is playing a key role in it.

As the academic year launched in late summer 2012, UFV hosted S’iwes Toti:lt Q’ep — Teaching and Learning Together, a conference with an Indigenizing the Academy focus, at its brand new longhouse-themed Aboriginal gathering place on the new Chilliwack campus at Canada Education Park. Over 275 participants from 33 post-secondary institutions across Canada attended.

Keynote speakers included well-known Aboriginal educators Joanne Episkenew and Eber Hampton, and the conference dinner was graced with an informal visit and talk by then–Lieutenant Governor Steven Point, a local Stó:lō person and UFV alumnus and honorary degree recipient.

The conference grew out of several years of development and activities aimed at indigenizing UFV, many of them inspired by the 2006 Indigenizing the Academy report authored by Stó:lō educator and consultant Mark Point after he consulted with the Aboriginal and UFV communities.

The report outlined a desire for UFV to develop an Indigenous Studies program, enhance Aboriginal research capacity, boost Aboriginal enrolment and improve retention and success of Aboriginal learners. It led to the creation of the senior advisor on indigenous affairs position, held by Shirley Hardman, who had previously been Aboriginal access coordinator.

UFV, located on traditional Stó:lō territory, has made it a formal practice to recognize and respect indigenous ways of knowing, and many public events are opened with a statement reflecting this. Nearly five percent of UFV’s student body self-identify as Aboriginal people. UFV’s Aboriginal Access Services department provides culturally appropriate delivery of services for current and prospective students, including an Elders-in-Residence program. The Senior Advisor on Indigenous Affairs provides leadership for the development of indigenous programs, the recruitment and retention of Aboriginal faculty and staff, and the development of strong links with Aboriginal communities.

Even prior to 2006, UFV had significant links with its local Aboriginal communities. It hired Theresa Neel as First Nations Access coordinator in the 1990s, opened its Aboriginal Access Centre in 2002, had an Aboriginal Community Council since 1997, and worked with the Stó:lō community on partnerships and programs since the 1970s. (In a coming-full-circle aside, Neel, who started out as a UFV student, then worked for UFV advising Aboriginal students, is now one of UFV’s elders-in-residence.)

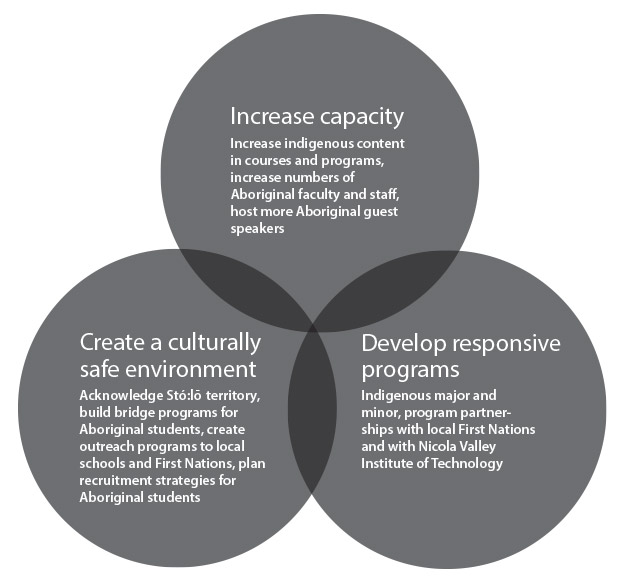

Mark Point’s 2006 report inspired the UFV Aboriginal Community Council to develop a strategic plan for Aboriginal relations at UFV entitled Indigenizing Our Academy. In October 2008, the UFV Board received three goals and accompanying actions. The plan itself is built around core values that were identified by the local community as values that guide a “good life.”

- Increase capacity (increase indigenous content in courses and programs, increase numbers of Aboriginal faculty and staff, host more Aboriginal guest speakers).

- Create a culturally safe environment (acknowledge Stó:lō territory, build bridge programs for Aboriginal students, create outreach programs to local schools and First Nations, plan recruitment strategies for Aboriginal students).

- Develop responsive programs (Indigenous major and minor, program partnerships with local First Nations and with Nicola Valley Institute of Technology).

Even with all this past, current, and future activity, the question of “what exactly does indigenizing mean?” arises.

Shirley Hardman, UFV’s senior advisor on Aboriginal affairs, is justifiably proud of the progress that has been made on indigenization at UFV, but she says the toughest challenge is finding ways to accommodate indigenous ways of knowing into the traditional academic structure.

“For me, indigenizing means creating an environment where we as Aboriginal people do not have to give up part of ourselves in order to take part in academia, and where we see ourselves reflected in the everyday life of the institution,” says Hardman, “It’s an environment where people easily make connections between the past and now, and see how events of the past two centuries have influenced indigenous peoples. It acknowledges a link between history and current social reality and prepares the next generation of professionals working with Aboriginal people to have a better understanding of all of that, as well as more empathy, whether they are Aboriginal themselves or not.”

Hardman asserts that people in power don’t set out to hurt Aboriginal students or negate Aboriginal culture, but that “the feeling of welcome and safety needs to be defined by those who use the service. We need to make universities natural places for Aboriginal people to be.”

UFV has already implemented courses and programs with local Aboriginal content, including courses in the Halq’eméylem language, Stó:lō history, and indigenous ways of knowing. It has run an Aboriginal carving certificate as part of the Visual Arts certificate. Last year’s Lens of Empowerment enabled students to use photography and video to explore the lives of women in Stó:lō territory. The new curriculum of the Practical Nursing program comes with a new emphasis on understanding the health care needs of Aboriginal populations, and fourth-year Bachelor of Science in Nursing students were placed in the Seabird Island Health Centre for an Aboriginal community health experience. The Indigenous Studies: Maps, Films, Rights, and Land Claims certificate is offered in partnership with the Stó:lō Nation. Social Services offers a First Nations option within its diploma program.

Recently Dr. Wenona Victor has been hired as the first faculty member designated to teach Indigenous Studies full time.

Victor’s role at UFV includes teaching Indigenous content courses in various disciplines, helping UFV implement the major/minor in Indigenous Studies, and working with the Office of Indigenous Affairs and Aboriginal Access Services to increase Indigenous student enrollment and programming.

“The key question as we move forward with indigenizing the academy is: How do you administer it?” says Hardman. “How do you arrange to have a master Aboriginal carver teach in a Visual Arts program for university credit when he doesn’t have an academic degree? How do we categorize an instructor who spent 15 years learning Halq’eméylem, an endangered language, so that she could teach it. She couldn’t take her training through a university, as no courses existed. Why can’t that be considered as good a preparation as a degree?”

Then there’s the challenging question of academic freedom. Can you require instructors to incorporate indigenous content or ways of knowing into their course curriculum?

Hardman is finding that educating faculty members about Aboriginal history and issues is an effective way of encouraging them to consider the Aboriginal perspective when building their courses. Also, it’s a hot property in the employment market.

“People who embrace the idea of indigenization are finding that they move forward in academia. There is a market for it.”

And she, adds, fear of offending is a major boundary to getting things done.

“One of the hardest things about indigenous curriculum development is that non-Aboriginal institutions are afraid of making a misstep as they try to make meaningful changes.”

So when they gathered by the hundreds for the S’iwes Toti:lt Q’ep — Teaching and Learning Together conference at UFV last summer, there were plenty of challenges for participants to discuss.

But it was evident that UFV’s senior administration is ready to listen and to adapt.

Dr. Mark Evered, president of UFV, opened the conference with a frank admission: “Far too many Aboriginal people find our campuses unwelcoming. Far too few are graduating from university. We need to change that, and we also need our non-Aboriginal students to graduate with a richer understanding of culture and heritage of our founding peoples, and for our faculty and staff to have a richer appreciation for it as well.”

Dr. Eric Davis, UFV provost and vice-president academic, explained that when he arrived at UFV more than 20 years ago, he was completely unaware of local Aboriginal culture.

“Growing up in the Jewish community in Montreal, then doing PhD studies in England, meant my upbringing left me extremely unprepared for the task of administering indigenization in the Fraser Valley. But I have learned. When I first arrived, nobody told me I’d come to the traditional territory of the Stó:lō people; now it is the first thing we say. As I became more aware, for first time in my life I felt like a colonizer. When I became an administrator, I became aware that I had an obligation to change the way the university operated.

“But how do you reconcile university administrative practices with indigenous governance? How do you undo 200 to 500 years of colonialism, including an educational system largely dominated by harm and abuse?

“People like me have to undo some of the training and education that we’ve got, unlearn what it means to be a university, and question our assumptions.”

Indigenizing the Academy keynote speaker Dr. Joanne Episkenew, director of the Indigenous Peoples’ Health Centre in Saskatchewan, likened the work of those trying to indigenize the academy to the folks on TV who investigate scientific myths.

“We are the indigenous myth busters — first the academy, and then the world!”

She then went on to say that Aboriginal people often are living the social issues that are talked about at an academic level. She herself has two grandchildren living with her.

“And similar to my grandchild feeling she has to ask the white kids if she can play with them and sometimes they say no, we still find we have to ask if we can play with the academy.”

She added that the model that said “to succeed you must be like us” — embodied in the residential school system and foster care, didn’t work.

She added that the model that said “to succeed you must be like us” — embodied in the residential school system and foster care, didn’t work.

Dr. Lynn Davis, another presenter at the Indigenizing the Academy conference and director of the Native Studies PhD program at Trent University, added that simply learning more about Aboriginal history changes peoples’ minds.

“When people learn the history of treatment of Aboriginal people in Canada, what actually happened, their world shifts! There are ‘aha’ moments when they hear about blankets infected with smallpox, and about laws that prevented Aboriginal people from having a lawyer.”

Aboriginal education pioneer Dr. Eber Hampton noted that “Education in the western tradition was more like subtraction than addition. There were parts of me I had to check at the door!”

And UFV elder-in-residence Eddie Gardner reminded the conference audience that Aboriginal culture is an evolving entity.

“When we look at Aboriginal culture we often think of it as something stuck in the past, pre-contact, yet we as a people adapt! We look at new realities.”

Dr. Steven Point, who at the time of the conference was winding up his term as lieutenant governor of British Columbia, attended the dinner celebration (at which several of his young relations danced), with his wife Gwen, who is a UFV faculty member.

He said he was glad we have arrived at a time when questions are being asked about indigenizing the academy, and reminded the audience that it is the grassroots level that education is needed the most, and that a huge challenge is seeing that primary-level students in isolated communities get the resources they need.

“The key is making sure the little kids of Kingcome Inlet can get educated.”

He then mused on the dynamic tension between people needing to leave their home communities to gain access to education and employment, and wanting to stay close to home to stay connected to their culture.

“Are we teaching people how to be a successful person in mainstream Canadian society or how to be successful in our own communities so that we can stay home?” he asked. “Indigenous people have something wonderful to offer this world.

It’s not just a question of how to indigenize the academy, but how to indigenize Canada! Indigenous people have some wonderful things to offer this world. Leave your communities if you must, but take your feathers and red paint with you, and remember the elders’ advice!”

For anyone new to academia, there’s a bit of confusion and trepidation.

Why do the professors wear those gowns at Convocation? How do you know when and where to apply for a scholarship? What’s a graduate degree?

For Aboriginal students, the gap between their worldview and mainstream academic culture can be even wider. Throw in decades of systemic racism within Canadian society; the devastating experience of many families with residential schools, foster care, and adoption outside of their communities; and the misrepresentation and stereotyping of Aboriginal people in the dominant historical narrative, and you have a lot of reasons for them to be wary of post-secondary education.

A growing number of universities and colleges are recognizing the need to make their campuses welcoming places for Aboriginal cultures, their knowledge and their learners. The formal name for the process is indigenization, and UFV is playing a key role in it.

As the academic year launched in late summer 2012, UFV hosted S’iwes Toti:lt Q’ep — Teaching and Learning Together, a conference with an Indigenizing the Academy focus, at its brand new longhouse-themed Aboriginal gathering place on the new Chilliwack campus at Canada Education Park. Over 275 participants from 33 post-secondary institutions across Canada attended.

Keynote speakers included well-known Aboriginal educators Joanne Episkenew and Eber Hampton, and the conference dinner was graced with an informal visit and talk by then–Lieutenant Governor Steven Point, a local Stó:lō person and UFV alumnus and honorary degree recipient.

The conference grew out of several years of development and activities aimed at indigenizing UFV, many of them inspired by the 2006 Indigenizing the Academy report authored by Stó:lō educator and consultant Mark Point after he consulted with the Aboriginal and UFV communities.

The report outlined a desire for UFV to develop an Indigenous Studies program, enhance Aboriginal research capacity, boost Aboriginal enrolment and improve retention and success of Aboriginal learners. It led to the creation of the senior advisor on indigenous affairs position, held by Shirley Hardman, who had previously been Aboriginal access coordinator.

UFV, located on traditional Stó:lō territory, has made it a formal practice to recognize and respect indigenous ways of knowing, and many public events are opened with a statement reflecting this. Nearly five percent of UFV’s student body self-identify as Aboriginal people. UFV’s Aboriginal Access Services department provides culturally appropriate delivery of services for current and prospective students, including an Elders-in-Residence program. The Senior Advisor on Indigenous Affairs provides leadership for the development of indigenous programs, the recruitment and retention of Aboriginal faculty and staff, and the development of strong links with Aboriginal communities.

Even prior to 2006, UFV had significant links with its local Aboriginal communities. It hired Theresa Neel as First Nations Access coordinator in the 1990s (she had previously served as an educational advisor for First Nations students), opened its Aboriginal Access Centre in 2002, had an Aboriginal Community Council since 1997, and worked with the Stó:lō community on partnerships and programs since the 1970s. (In a coming-full-circle aside, Neel, who started out as a UFV student, then worked for UFV advising Aboriginal students, is now one of UFV’s elders-in-residence.)

Mark Point’s 2006 report inspired the UFV Aboriginal Community Council to develop a strategic plan for Aboriginal relations at UFV entitled Indigenizing Our Academy. In October 2008, the UFV Board received three goals and accompanying actions. The plan itself is built around core values that were identified by the local community as values that guide a “good life.”

The three goals are to:

- Increase capacity (increase indigenous content in courses and programs, increase numbers of Aboriginal faculty and staff, host more Aboriginal guest speakers).

- Create a culturally safe environment (acknowledge Stó:lō territory, build bridge programs for Aboriginal students, create outreach programs to local schools and First Nations, plan recruitment strategies for Aboriginal students).

- Develop responsive programs (Indigenous major and minor, program partnerships with local First Nations and with Nicola Valley Institute of Technology).

Even with all this past, current, and future activity, the question of “what exactly does indigenizing mean?” arises.

Shirley Hardman, UFV’s senior advisor on Aboriginal affairs, is justifiably proud of the progress that has been made on indigenization at UFV, but she says the toughest challenge is finding ways to accommodate indigenous ways of knowing into the traditional academic structure.

“For me, indigenizing means creating an environment where we as Aboriginal people do not have to give up part of ourselves in order to take part in academia, and where we see ourselves reflected in the everyday life of the institution,” says Hardman, “It’s an environment where people easily make connections between the past and now, and see how events of the past two centuries have influenced indigenous peoples. It acknowledges a link between history and current social reality and prepares the next generation of professionals working with Aboriginal people to have a better understanding of all of that, as well as more empathy, whether they are Aboriginal themselves or not.”

Hardman asserts that people in power don’t set out to hurt Aboriginal students or negate Aboriginal culture, but that “the feeling of welcome and safety needs to be defined by those who use the service. We need to make universities natural places for Aboriginal people to be.”

UFV has already implemented courses and programs with local Aboriginal content, including courses in the Halq’eméylem language, Stó:lō history, and indigenous ways of knowing. It has run an Aboriginal carving certificate as part of the Visual Arts certificate. Last year’s Lens of Empowerment enabled students to use photography and video to explore the lives of women in Stó:lō territory. The new curriculum of the Practical Nursing program comes with a new emphasis on understanding the health care needs of Aboriginal populations, and fourth-year Bachelor of Science in Nursing students were placed in the Seabird Island Health Centre for an Aboriginal community health experience. The Indigenous Studies: Maps, Films, Rights, and Land Claims certificate is offered in partnership with the Stó:lō Nation. Social Services offers a First Nations option within its diploma program.

Recently Dr. Wenona Victor has been hired as the first faculty member designated to teach Indigenous Studies full time.

Victor’s role at UFV includes teaching Indigenous content courses in various disciplines, helping UFV implement the major/minor in Indigenous Studies, and working with the Office of Indigenous Affairs and Aboriginal Access Services to increase Indigenous student enrollment and programming.

“The key question as we move forward with indigenizing the academy is: How do you administer it?” says Hardman. “How do you arrange to have a master Aboriginal carver teach in a Visual Arts program for university credit when he doesn’t have an academic degree? How do we categorize an instructor who spent 15 years learning Halq’eméylem, an endangered language, so that she could teach it. She couldn’t take her training through a university, as no courses existed. Why can’t that be considered as good a preparation as a degree?”

Then there’s the challenging question of academic freedom. Can you require instructors to incorporate indigenous content or ways of knowing into their course curriculum?

Hardman is finding that educating faculty members about Aboriginal history and issues is an effective way of encouraging them to consider the Aboriginal perspective when building their courses. Also, it’s a hot property in the employment market.

“People who embrace the idea of indigenization are finding that they move forward in academia. There is a market for it.”

And she, adds, fear of offending is a major boundary to getting things done.

“One of the hardest things about indigenous curriculum development is that non-Aboriginal institutions are afraid of making a misstep as they try to make meaningful changes.”

So when they gathered by the hundreds for the S’iwes Toti:lt Q’ep — Teaching and Learning Together conference at UFV last summer, there were plenty of challenges for participants to discuss.

But it was evident that UFV’s senior administration is ready to listen and to adapt.

Dr. Mark Evered, president of UFV, opened the conference with a frank admission: “Far too many Aboriginal people find our campuses unwelcoming. Far too few are graduating from university. We need to change that, and we also need our non-Aboriginal students to graduate with a richer understanding of culture and heritage of our founding peoples, and for our faculty and staff to have a richer appreciation for it as well.”

Dr. Eric Davis, UFV provost and vice-president academic, explained that when he arrived at UFV more than 20 years ago, he was completely unaware of local Aboriginal culture.

“Growing up in the Jewish community in Montreal, then doing PhD studies in England, meant my upbringing left me extremely unprepared for the task of administering indigenization in the Fraser Valley. But I have learned. When I first arrived, nobody told me I’d come to the traditional territory of the Stó:lō people; now it is the first thing we say. As I became more aware, for first time in my life I felt like a colonizer. When I became an administrator, I became aware that I had an obligation to change the way the university operated.

“But how do you reconcile university administrative practices with indigenous governance? How do you undo 200 to 500 years of colonialism, including an educational system largely dominated by harm and abuse?

“People like me have to undo some of the training and education that we’ve got, unlearn what it means to be a university, and question our assumptions.”

Indigenizing the Academy keynote speaker Dr. Joanne Episkenew, director of the Indigenous Peoples’ Health Centre in Saskatchewan, likened the work of those trying to indigenize the academy to the folks on TV who investigate scientific myths.

“We are the indigenous myth busters — first the academy, and then the world!”

She then went on to say that Aboriginal people often are living the social issues that are talked about at an academic level. She herself has two grandchildren living with her.

“And similar to my grandchild feeling she has to ask the white kids if she can play with them and sometimes they say no, we still find we have to ask if we can play with the academy.”

She added that the model that said “to succeed you must be like us” — embodied in the residential school system and foster care, didn’t work.

Dr. Lynn Davis, another presenter at the Indigenizing the Academy conference and director of the Native Studies PhD program at Trent University, added that simply learning more about Aboriginal history changes peoples’ minds.

“When people learn the history of treatment of Aboriginal people in Canada, what actually happened, their world shifts! There are ‘aha’ moments when they hear about blankets infected with smallpox, and about laws that prevented Aboriginal people from having a lawyer.”

Aboriginal education pioneer Dr. Eber Hampton noted that “Education in the western tradition was more like subtraction than addition. There were parts of me I had to check at the door!”

And UFV elder-in-residence Eddie Gardner reminded the conference audience that Aboriginal culture is an evolving entity.

“When we look at Aboriginal culture we often think of it as something stuck in the past, pre-contact, yet we as a people adapt! We look at new realities.”

Dr. Steven Point, who at the time of the conference was winding up his term as lieutenant governor of British Columbia, attended the dinner celebration (at which several of his young relations danced), with his wife Gwen, who is a UFV faculty member.

He said he was glad we have arrived at a time when questions are being asked about indigenizing the academy, and reminded the audience that it is the grassroots level that education is needed the most, and that a huge challenge is seeing that primary-level students in isolated communities get the resources they need.

“The key is making sure the little kids of Kingcome Inlet can get educated.”

He then mused on the dynamic tension between people needing to leave their home communities to gain access to education and employment, and wanting to stay close to home to stay connected to their culture.

“Are we teaching people how to be a successful person in mainstream Canadian society or how to be successful in our own communities so that we can stay home?” he asked. “Indigenous people have something wonderful to offer this world.

It’s not just a question of how to indigenize the academy, but how to indigenize Canada! Indigenous people have some wonderful things to offer this world. Leave your communities if you must, but take your feathers and red paint with you, and remember the elders’ advice!”

Comments are closed.