With tongue firmly in cheek (which is just where it should be in this case), Professor Turner celebrates the connections between cured meats and great stories . . .

By Hilary Turner

Photo Credit: Instant Vantage Flickr via Compfight cc

Photo Credit: Instant Vantage Flickr via Compfight cc

Today as we celebrate National Salami Day we are conscious that salami, despite its many virtues, has not always been recognized as an especially healthy comestible—nor indeed does it figure prominently in many diet plans, or often appear with approving asterisks on lists of medically recommended foods.

Sadly, I do not believe that among the popular diets of today there exists such a thing as the salami diet. Salami is, nevertheless, a chewy, robust, greasy, and entirely respectable form of nourishment. It appeals especially to those charming young folk who care nothing for the smell of their breath, the (eventual) size of their waistlines, or their blood-pressure in midlife.

Dictionarily, salami is situated between salamander (a sort of lizard) and sal ammoniac (a poison). This is a mere matter of chance—language being largely a matter of chance—and it should not prejudice our response to its definition as “a kind of sausage, highly spiced or flavoured with garlic.” Yet this description, however informative, is rhetorically barren.

But what of salami in literature? Surely it is here that we will gain a more nuanced understanding!

Admittedly, there isn’t much to go on. The Roman poet Horace exclaims “Odi profanum vulgus et salami”—signifying, more or less, that he hates the common salami-chewing crowds and would prefer to chill at home. The nineteenth-century British novelist Charles Dickens is a little more forthcoming: he has the unredeemed Ebenezer Scrooge characterize the ghost of his former partner Jacob Marley as “an undigested bit of salami, a blot of mustard, a crumb of cheese, a fragment of underdone potato.” John Milton did not approve of salami and refused to mention it anywhere in Paradise Lost. George Eliot’s opinion of salami is unknown, but she too is silent on the subject in both Middlemarch and The Mill on the Floss. It is just as well: these books are long enough already. The letters of Samuel Beckett and Emily Dickinson reveal their mutual enjoyment of salami—or would, if they had lived at the same time and on the same continent.

For a fully contextual literary portrait of salami we must turn to a writer closer in time to our own. I refer to the American novelist Don Robertson (1929-1999) author of a dozen very good books and a handful of bad ones.

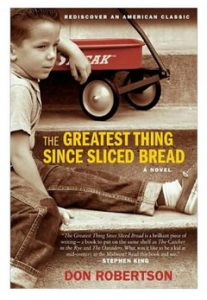

Among the former is The Greatest Thing Since Sliced Bread (1965) which, by title alone, would seem to put us in the right dietary neck of the woods. The title, alas, does not refer to salami itself, but to the novel’s protagonist, the eight-year-old Morris Bird III, who is extolled in these ringing words by a legless trumpet player whom Morris has rescued from the aftermath of a massive gas explosion in Cleveland in 1944.

And Morris Bird III is the greatest. He is courageous, inventive, determined, and unselfish. He is also a person of tender conscience—as is revealed (and now we come to it) in the salami sandwich incident of the previous year.

One fateful day, instead of his usual peanut butter and jelly concoction, Morris Bird III has found in his lunch bag a Thing:

There it was, staring up at him, this Thing.

…

It lay thinly between two stale slices of rye bread. Spots and blobs of mayonnaise hung out. It smelled like bad breath….It had white spots on it.

Unable even to contemplate eating the Thing, Morris tries to give it to a boy named Alex Coffee, also known as The Human Garbage can. But Alex Coffee will have none of it. Through no one’s fault in particular, the Thing is tossed aside—only to turn up a few paragraphs later colourfully decorating one side of the car that belongs to Mrs. Clementine Ochs, the school principal.

So far from being amused is Mrs. Ochs that she launches an investigation—“a ceaseless and surpassingly thorough investigation that eventually would be successful. No such horrible secret could be kept forever.”

With amazing fortitude, Morris does keep the secret. This, despite the fact that at his first refusal to “stand forward” for a crime he has not in fact committed, “something with long scraggly teeth went to work chewing on his insides.” He pays dearly for his silence with a week-long internal agony, as he is torn between terror, guilt, and self-recrimination. He is prone to attacks of nausea and vomiting. He cannot sleep. He tortures himself with thoughts of fingerprints. And he watches in horror as the great Salami Inquisition takes its unremitting course. Others are accused of the evil deed; these others deny it, some tearfully, some defiantly. At last, he can stand it no longer and Morris Bird III presents himself tremblingly at the office of Mrs. Clementine Ochs.

In this marvellous episode, whose surprising conclusion I will not reveal, we see shine forth the true literary potential of salami. Far more than a plot device, salami here comes into its own as an awesome and complex symbol. A symbol of what? Of the inequalities of power that exist between adults and children. Of the intricacies and tortures of conscience. Of the monstrous effects of shame. Of the operations of justice itself.

What better day than today, National Salami Day, to begin to explore the novels of Don Robertson?

The Morris Bird III trilogy (consisting of The Greatest Thing Since Sliced Bread, The Sum and Total of Now, and The Greatest Thing That Almost Happened) has been reissued in paperback by Harper Collins. Robertson’s other books are out of print—some are rare and quite expensive—but can still be found at ABE books, and on eBay.

Comments are closed.