Nadeane Trowse contributes our next Every Day English blog post to commemorate Freedom to Read Week.

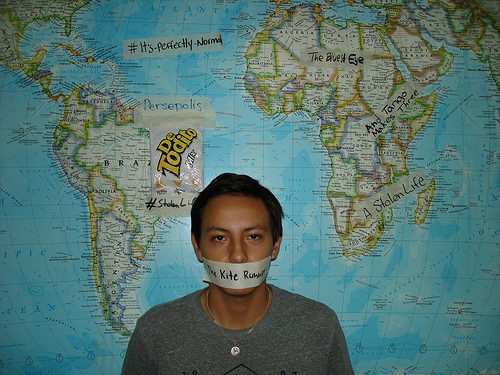

Photo Credit: americanobiblioteca Flickr via Compfight cc

Photo Credit: americanobiblioteca Flickr via Compfight cc

When freedom to read is only the necessary start

I was ten when I read a portion of a banned book.

My great aunt (who valued ‘culture’), gave a mimeographed copy of part of Lady Chatterley’s Lover to my mother (who did not). I was not an intended reader or even an intended prohibited reader for the document but ten-year-olds have ways to quietly take things out of knitting bags when others are napping. This occurred just after the legal ban was lifted, but when copies of the book had not quite made it to BC’s west coast. Thus it bore just enough of the luster of forbiddenness to enliven morning coffee conversations.

But I found it boring. The idea of a gamekeeper-hero had suggested to me that a reader might learn things about, well, game-keeping and I was interested in pheasants and quail. Interest generated by the extra – the slightly lurid glow, and knitting bag concealment – wasn’t in the end about the book but about the contest of who got to decide, not on the possible harms from explicit content, but on the rights and freedoms of publishers to profit.

In that setting, freedom to read meant the right to plan and organize my own reading, in the face of obstacles.

Freedoms are beset by obligations, even dangers: you can or cannot read A but you must or must not read B. Literacy is the enabler, somehow loosely joined to the freedom/reading connection.

I think of the contests around the right to read in Our Mutual Friend (never a banned book, but its present small-ish readership caused by length or era of production, perhaps). In it, Charlie Hexam “gives away” the dangerous information that he actually can read, just by the way he looks at a bookshelf, in spite of his dreadful father’s prohibition against learning. His “reading” look condemns him. Gaffer Hexam, his father, is “a bird of prey” who displays his prodigious memory to show up the gentry with their effortless airs of superiority and also to discount the value of reading. His alternative skill is reading the river to which he owes his living and any non-river related reading or “reading” he domestically banned, not by the removal of troublesome texts, but by prohibiting the education to get the skills needed to access any other kinds of texts. But Charlie’s saintly sister has secretly enabled him to get “a little learning” which costs, and yields a very mixed crop of liberation through literacy skills.

What Charlie learns as he rises from being a marginalized poor child at a very marginal school, through his ascension from the ranks of teacher’s helper to full fledged teacher with a school of his own, is to re-read and censure his own experience. Reading has made him sensitive to his rights but not how he got them. He re-reads his sister’s support as a natural guaranty of her subordination. He re-reads his freedom to learn to read as a personal character attribute, not a gift given him by his sister who saw literacy as a way to liberate him from the harshest of Victorian society.

Dickens does not give readers a glimpse of what Charlie liked to read, or indeed what kinds of texts he used in his turn to teach his pupils. Exam crib sheets, I could imagine, made up his preferred reading. With a “refresher of the principle rivers of Europe,” followed by a stock market report. He might have had the freedom to read, but he also has the freedom to NOT use his hard come by literacy to read anything likely to be worth reading beyond what might be needed to teach. Moreover, he is good at prohibiting all alternate readings in his world that do not support his self-congratulatory self image.

What I am getting at, what the “more” than freedom to read needs, perhaps, is that the freedom to read needs to be linked with the reasons to read materials which might be vulnerable to prohibition.

Maybe it has something to do with “heart”.

Comments are closed.