Salwar Kameez

The quintessential South Asian coupling of wide trousers cuffed around the ankles with a straight-cut, long tunic.

Chandra Bodalia’s collection of photographs opened the Pandora’s box of my childhood memories: of my dadi holding embroidered salwar kameez too close to the camera for Skype to capture its detail, of my chachi trying pull the clothing back so we could actually see it, of my cousin poking in on the side to ask what we thought, of my chacha promising to pass them off to my dad’s friend of a friend who has been tasked with bringing a suitcase full of clothing from Karachi, Pakistan to a small city in Ontario.

During the early 2000s, the most common way my parents would procure South Asian clothing while in Canada, fancy or comfortable, was through the most lucrative trade channel of all time: family and friends travelling from South Asia. Back then, check-in bags used to be included in the ticket price!

The most convenient way, however, was to purchase them from aunties who had turned their spare bedrooms into boutique stores and set up stalls at Eid fairs with beautiful salwar kameez, sarees, lehengas, and anarkalis hanging from the clothing racks. But, you had to be savvy and quick-witted around those aunties because they were definitely overcharging; they brought the spirit of a bazaar home by creating the absolute need to haggle.

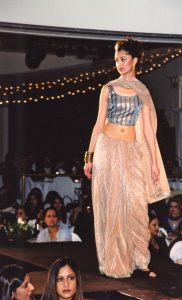

Lehenga Choli

Lehenga Choli

The glamorous combination of a long, pleated skirt with a matching blouse, accompanied by a dupatta.

Of course, Bodalia had not been photographing the hilarious ordeal of two kids standing on an overflowing suitcase full of skirts and blouses while an uncle desperately tries to zip it shut, nor did he capture the pure delight on mamas’ and aunties’ faces when they opened up these suitcases to find intricate, fancy lehengas and comfortable, homey salwar kameez.

But he did immortalize South Asian fashion in British Columbia with every shutter of his lens.

I catalogued approximately forty envelopes showcasing fashion shows, starting from the late 1990s to the early 2000s, across a minimum of five distinct events. These shows seemed to be specifically linked to charity and fundraising events, as well as beauty pageants, with the exception of one show that was explicitly to showcase the work of a Surrey-based fashion brand still in operation to this day, Armaan.

Each envelope displayed runways upon runways of South Asian Canadians modelling glitzy lehenga cholis, elegant sarees, shiny sharara suits, flowy anarkali dresses, embroidered kurtas, and fitted sherwanis. Many of the models were sporting beaded, sparkling, matching and contrasting dupattas that hung off their shoulders or wrapped around their necks as the perfect accessory.

Quite a few of the catalogued fashion shows also incorporated a dance or drama element. They melded the visual star power of South Asian clothing with the South Asian flair for entertainment, ultimately creating the most immersive experience for everyone in the audience.

Each model was confident and comfortable in South Asian clothing. You could just feel their energy and movement through the photographs since every stride, every turn, every twirl, and every pose was printed on crisp, glossy four-by-sixes.

They were the embodiment of everything young South Asian Canadians quietly wished to be: unrelenting and proud to be South Asian, proud to be wearing South Asian clothes outside of the privacy of home.

Sharara Suit

A set of flowy, flared skirt-like pants, paired with a long kurta and dupatta.

Those of us from the Lower Mainland are quite familiar with the Punjabi Market in Vancouver, British Columbia, which spans the commercial area of Main Street around 49th Avenue, and houses South Asian restaurants, clothing stores, and grocery stores, among others. It might be less well known that the first shop to establish the Punjabi Market was a South Asian clothing and fabric store: Shaan Sharees and Drapery, opened by Sucha Singh Claire and Harbans Kaur Claire on May 31, 1970. The Claires noticed that South Asians would wear Western attire during cultural activities because there were no South Asian clothing stores in the area, so they opened Shaan Sharees and Drapery to address the needs of their community, and soon the Punjabi Market flourished.

Sucha Singh Claire may have retired in 1995, but the demand for South Asian clothing in Canada has only risen. South Asian clothing stores have been planting roots all across the Lower Mainland and have garnered attention in the media for their past and future endeavours, such as Surrey-based Crossover Bollywood Se, Vancouver-based aselectfew, and Surrey-based Armaan DBG. Photographs of Armaan DBG’s beautiful and unique designs, worn by South Asian models, from their fashion shows can be found in Bodalia’s collection.

Anarkali Dress

A youthful and flattering dress formed from an embellished top-turned-frock, accompanied by a churidar and a dupatta.

The appropriation of South Asian culture, especially our clothing, by Western bodies is not a new phenomenon. It remains a largely divisive topic among South Asians, as it often circles arguments where many first-generation South Asian Canadians view any engagement with South Asian culture as a positive opportunity to share their culture, versus where many second-generation South Asian Canadians remain skeptical of the intentions behind non-South Asians engaging with our culture.

There is also the never-ending question about whether something is appropriation or simply heavily inspired by South Asian culture. If it is the latter, where is the awareness and/or acknowledgement of such inspiration?

With the recent and continuous rise of anti-South Asian sentiments in Canada, we have to ask: Why do non-South Asians feel comfortable adopting elements of our fashion and culture, such as bindis and dupattas, going as far proclaiming them to be “Scandinavian scarves,” when South Asian Canadians have been discriminated against and ridiculed for wearing their own cultural clothing?

There is no easy answer for this double standard; some may see it as a compliment, and others might understand it to be a slight.

Regardless, South Asian clothing has centuries worth of rich history, and its designs remain timeless and evolving. Like the models from the fashion shows in Bodalia’s collection, South Asian Canadians will continue to showcase these intricate styles and patterns, whether in their homes, at cultural celebrations, at weddings, and at fundraisers.

This history and appreciation is something that can never be stolen from South Asian Canadians.

Kurti

A contemporary spin on the ethnic Kurta, now shortened and fitted, yet equally intricate and adorned.

Even in the face of anti-South Asian sentiments and cultural appropriation, South Asian fashion has been receiving its flowers as it steadily makes its way into “mainstream” fashion spaces.

There is a notable shift in mentality, specifically among second-generation South Asian Canadians, whereby we are no longer hiding our South Asian clothing in stuffed suitcases and only taking them out for religious celebrations or shaadis.

South Asian influencers on social media have begun embracing and uplifting the cultural elements that make them South Asian, with a particular focus on fashion. Events such as South Asian Fashion Week are being hosted in the Lower Mainland, with the goal of promoting and showcasing South Asian fashion in its traditional representations and as fusion pieces. There are many initiatives which are actively moving away from the belief that South Asian clothing can only be worn in South Asia or that South Asian Canadians can only experience it through Bollywood movies.

Jeans with kurtis, a staple combo in India and Pakistan, are finally being normalized in North America! South Asian Canadians are finding ways to incorporate South Asian clothing into their daily or fancy attire, including unique ways to style a dupatta or wearing down a lehenga skirt with a casual top.

It is a beautiful progression to witness.

As I live through this shifting space, I find myself reflecting back on how Bodalia’s collection opened the Pandora’s box of my childhood. Growing up in the late 2000s – 2010s, I could not fathom wearing lehenga cholis or anarkali dresses outside of private, South Asian-only events.

It makes me wonder if those South Asian Canadians modelling their ethnic clothing in the late 1990s and early 2000s had similar thoughts? Despite walking with confidence, did they have doubts or insecurities about being adorned in South Asian clothing? Despite every embroidered top, every saturated garment, every reshmi dupatta being a showstopper, were these fashion shows the only opportunity for designers to show off the beauty of South Asian clothing in Canada? Did the organizers of these events ever consider how to introduce South Asian clothing to a non-South Asian audience?

Perhaps these issues were not as deep or poignant for them as they are for me, a young South Asian Canadian soon-to-be archivist trying to make sense of her identity and community through the 3 million+ photographs a single South Asian man from Vancouver captured.

But they felt meaningful to me as I flipped through envelope upon envelope of South Asian fashion for months.

Saree

Saree

A timeless and graceful garment draped around the waist, over a petticoat, and paired with a blouse.

Clothing is an expression of identity.

Bodalia’s collection not only features wonderful fashion shows, which specifically showcase the glamorous side of South Asian clothing, but also introduces less overt expressions through the clothing worn by South Asian performers from other events in the collection and the clothing worn by regular attendees of ceremonies and intimate gatherings.

Those with a keen eye would enjoy parsing through the collection, either to appreciate, research, or reflect on.

Every garment adorned in this collection speaks to the South Asian Canadian identity of the time, how it manifested, and how it was embodied.

As I pull out the sharara suit jammed at the bottom of an old suitcase, transported with me from my last visit to Pakistan, I wonder if the designers of the clothing, the models who wore them, the dancers who embodied them, and the organizers of these events could have even fathom being archived two decades later.

How must it feel to have yourself and your clothing be immortalized, digitized, and uploaded onto the South Asian Canadian Digital Archive?