Over the past several months, I’ve worked on two different archival projects that, while quite different, both focused on preserving and sharing the stories of underrepresented communities. The first involved co-cataloguing the Chandra Bodalia photographic fonds with a colleague. The second, which I undertook independently, involved transcribing, translating and researching a payroll ledger from the Mayo Lumber Company, with a focus on Japanese Canadian and Chinese Canadian workers in 1916-1917. These experiences taught me technical skills in archival description and transliteration, but more importantly, they showed me the importance of care, community, and critical reflection when working with records from underrepresented communities.

Cataloguing Chandra Bodalia fonds: Exploring moments of community life

Chandra Bodalia was a prolific photographer based in Vancouver with an extensive body of work. During the span of his career, Bodalia documented many community events, particularly within South Asian and IBPOC communities. My colleague and I spent several weeks cataloguing thousands of prints and negatives. At first, the images felt repetitive: group shots from the same community events, stage performances, fashion shows, and picnics. But as we kept going, a more layered and meaningful story started to take shape.

Chandra Bodalia was a prolific photographer based in Vancouver with an extensive body of work. During the span of his career, Bodalia documented many community events, particularly within South Asian and IBPOC communities. My colleague and I spent several weeks cataloguing thousands of prints and negatives. At first, the images felt repetitive: group shots from the same community events, stage performances, fashion shows, and picnics. But as we kept going, a more layered and meaningful story started to take shape.

I started noticing patterns in the photographs we handled, such as recurring guests participating in the event for consecutive years and intersections between South Asian and other immigrant communities. For example, photographs from multicultural events were taken repeatedly for several years and they showed important solidarities between South Asian and Chinese Canadian communities. These are details that may go unnoticed without close attention. This experience deepened my appreciation for archival records, highlighting how materials not originally intended for scholarly or historical purposes can nonetheless offer rich insight into lived experiences and patterns of social interaction.

In addition, Bodalia’s active role within the Asian Canadian communities undoubtedly meant he documented many moments of celebration and joy. These images of joyful occasions, such as Diwali celebrations, Punjabi Mela festivals offered a glimpse into the rich cultural fabric of the South Asian Canadian communities in Vancouver. For me, I felt an unexpected emotional connection to these images. There was an uplifting quality to the work, seeing numerous photographs of people dancing, laughing, hugging each other and simply enjoying their time. It made our work feel rewarding.

However, our work wasn’t always filled with light-hearted moments. At times, photographs were taken at events such as memorial services and other poignant moments of loss. These photographs carried a drastically different weight than those mentioned previously, and cataloguing them often led me to research the accidents they documented and reflect on the people in the photographs: their families, their communities, and their lives. While these images were not ethically challenging in the sense that they didn’t include depictions of victims, they captured great grief and a collective response to loss. Many of these photographs, for instance, show community members coming together to honor those lost in tragic accidents. Cataloguing them required not just awareness of their somber nature, but also reflection on the role of archival work itself. Archivists are not simply processing records; they are engaging with stories. Fortunately, SACDA designed the internship program with two placements, which allowed me to work alongside a colleague while cataloguing the photographs. While some of the images were indeed emotionally difficult to process, having someone else present made the work more manageable.

Independent research: Reconnecting with my heritage

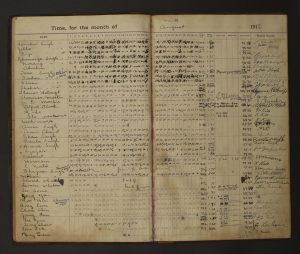

While the Bodalia project emphasized collaboration, my work on the Mayo Lumber Company ledgers was entirely independent. These ledgers recorded Japanese Canadian and Chinese Canadian workers, noting their names, hours and wages. My goal was to carry on with the previous students’ work and continue transcribing these names and where possible, provide an appropriate translation into kanji characters (for Japanese names) and Jyutping transcriptions (for Cantonese/Chinese names).

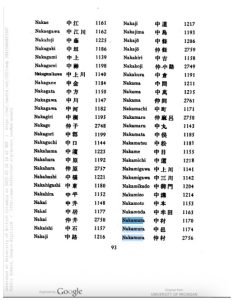

The romanizations in the ledger were inconsistent and lacked indicators such as long vowels or diacritics, making it difficult to accurately reconstruct the original kanji. Several possibilities might explain this: perhaps diacritics were not commonly used in the early 1900s; perhaps the record keepers omitted them, intentionally or otherwise; or perhaps the names simply did not include long vowels to begin with. The absence of these markers adds significant ambiguity. For example, without long vowels, the name “Oda” could easily be mistaken for “Ōta” , which are two entirely different names with distinct meanings: Oda 小田 (small field) and Ōta 大田 (large field). To address this uncertainty and avoid making any uninformed guesses, I turned to historical resources like Japanese Surnames (1943), which was considered a comprehensive work on Japanese surnames in its time, and examined naming conventions from the early 20th century. With reference to this book, I included all possible translations in my work to ensure comprehensive coverage.

Fig. 1 A page from Japanese Surnames (1943), showing examples of names with the same pronunciation but written with different kanji characters, e.g., “Nakamura” at the bottom of the second column.

In contrast to the Japanese names, the Chinese names presented a different set of challenges. Romanization systems for Cantonese vary significantly, from older systems like Wade-Giles and Yale to the more recent Jyutping. Each system represents sounds differently, and none is used universally. After weighing the options, I chose Jyutping for its tonal precision, consistency, and alignment with how Cantonese is spoken and taught today (粵拼 Jyutping, n.d.). Unlike Wade-Giles, which was originally developed for Mandarin and lacks tonal clarity, Jyutping was designed specifically for Cantonese and uses a standardized structure that reduces ambiguity, making it more accessible for both learners and users. To familiarize myself with the system, I read articles, watched tutorials, and studied the phonetic rules of Jyutping. Although Cantonese is my first language and I was born and raised in Hong Kong, I had never formally studied it in a classroom setting as it is not part of the standard curriculum. Like many Hongkongers, I realized my understanding of how to write and pronounce words correctly was limited. Learning Jyutping pushed me to engage with Cantonese more analytically, almost as if I were learning it as a second language! It was both a challenging and fascinating process, one that ultimately helped me reconnect with my roots and reflect on my identity, which was shaped by growing up during the later phase of British colonial rule and into post-colonial Hong Kong.

Fig. 2 A screenshot of the website “粵拼 Jyutping”.

Moving Forward

In June 2025, we will present our experience working with the Chandra Bodalia photographic fonds at the ACA conference. Our presentation will focus on the structure of the internship program and the collaborative process of co-cataloguing. We aim to highlight how SACDA’s support enabled student interns to take on meaningful community archival work and how working in a small group not only enhanced the quality and depth of the work but also created space for reflection, dialogue and shared decision-making.

Overall, this internship has been more than just a professional opportunity. It’s been a deeply personal journey. Working on the Chandra Bodalia fonds and the Mayo Lumber Ledger challenged me to think critically about representation, language, and identity in archival work. It has given me new skills, a deeper sense of self, and a lasting belief in the importance of community-driven archival practices.

References

Gillis, I. V., & Pai, P. (1943). Japanese personal names. Edwards Bros.

Why should we use Jyutping instead of other Cantonese romanizations?. 粵拼 Jyutping. (n.d.). https://jyutping.org/en/blog/scheme/.