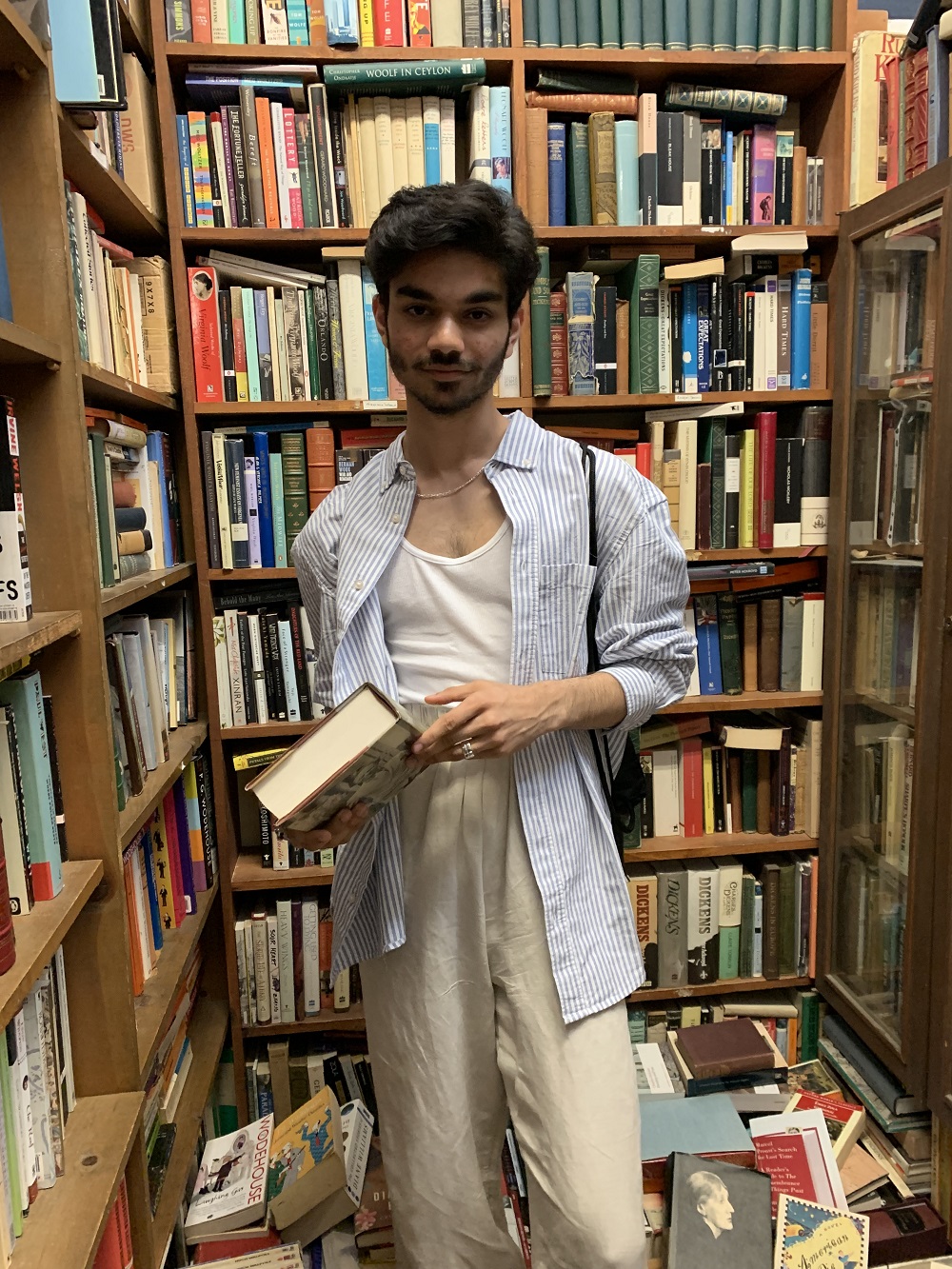

Prabhpreet Singh Gill is a 16 year old student-athlete from Rick Hansen Secondary School. His passion for Sikh history and Punjabi culture led him to volunteer with the South Asian Studies Institute at UFV as an intern. When he isn’t working in building F, you can find him hiking, swimming or binge watching Netflix. He is an active role model at school as he is a part of the Student Government and Leadership, Creative Director in Yearbook, Vice President of Global Awareness and an active member of the RHSS Concert Band. Out of school, he is the Chief Operations Officer of the BC Youth Council, Creative Director at The Diversity Story, a US based publication that focuses cultural awareness, National Advisory Council member of FBLA Canada, a financial literacy organization based in Toronto that helps youth learn about financial literacy through workshops, webinars and activities.

Prabhpreet Singh Gill is a 16 year old student-athlete from Rick Hansen Secondary School. His passion for Sikh history and Punjabi culture led him to volunteer with the South Asian Studies Institute at UFV as an intern. When he isn’t working in building F, you can find him hiking, swimming or binge watching Netflix. He is an active role model at school as he is a part of the Student Government and Leadership, Creative Director in Yearbook, Vice President of Global Awareness and an active member of the RHSS Concert Band. Out of school, he is the Chief Operations Officer of the BC Youth Council, Creative Director at The Diversity Story, a US based publication that focuses cultural awareness, National Advisory Council member of FBLA Canada, a financial literacy organization based in Toronto that helps youth learn about financial literacy through workshops, webinars and activities.

Although I am in my adolescent years learning more about the world, I have always been exposed to the systemic world of caste. Ever since my early childhood years, I have adored Punjabi music as its upbeat tunes and rhythms never fail to boost my serotonin. But as I have become more mature and aware of the lyrics, I was surprised by the constant usage of the caste name “Jatt” in most of the mainstream Punjabi music. It is as if utilizing Jatt in their songs upholds power and entitlement over other individuals. Punjabi media’s obsession with caste has led me to a rabbit hole of understanding its true relevance in modern day society given that the Sikh religion espouses equality amongst everyone.

I remember asking my Nanaji (maternal grandfather) if we were Jatt and what made us Jatt? And although he tried his best to explain, I never truly understood the concept of being “better” than someone due to a meaningless title.

This obsession soon became prevalent in high school as I noticed how Jatt-Sikhs, especially males, would harass other non-jatts by their surname or caste. It was almost as if a small plague trickled down and began to infect everyone. I was blown away by how much pride and gratification my peers would take in being a part of a caste that our culture glorifies. Although I do not blame them for their actions, partly due to the exposure of Punjabi media, a greater lack of awareness and the lack of family dialogue, I do believe that being more literate about systemic issues that originated thousands of years ago is vital for society to move forward in an inclusive manner. This pride in owning a position of caste, soon led to the arrogance of some students as their negative influences and behaviors would result in them saying “koina, apa Jatt aa” which translates to “it’s all ok, because we are Jatt”. The word itself built its own complex meaning of being egotistical while promoting the invisible barrier of protection from consequences.

The constant question of “what caste are you?” has been a conversation starter for countless Punjabi students. But if the reply is anything other than Jatt, the potent essence of judgment emanates from within the room. Whenever I get asked the question, I just say that I do not believe in the caste system, but I believe in Sikhism and our religion has never and WILL never ask us to follow a system of hierarchy. But in return, people would just rather believe that I am not a Jatt because I choose not to disclose my title.

The implications of being a part of a caste that is not idolized can deteriorate one’s mental health and self-confidence. Constantly being reminded of your caste and how you do not fit in can leave lifelong trauma that can take years to just discover and heal. Observing my peers of a “lesser caste” fall under this trap breaks my heart as they just want to be valued and accepted. I have seen countless students from across Abbotsford not disclose their caste as they are ashamed of where they come from and who they associate with. In particular, a female within my school who is a brahmin is constantly asked the question “are you a Jatt or not?” Her facial expressions show the discomfort and sadness she feels yet she answers with a simple no. Her resilience, intelligence and keen personality gets thrown out of the window just due to the fact she’s not one of “us”. Her experiences with caste are more contrasted than those who are privileged by it. This too, is made more complex by the fact the caste system stems from a Brahmanical power structure, and is not foundationally found within the Sikh faith.

Her experiences make me question, what does it really mean to be a Jatt? Is it bragging rights? Power? Strong affiliations? What does it mean to be a Jatt in today’s world even? Is being associated with a caste really something our identity connects to or is it something society has just led us to believe? These questions led to a deeper curiosity for me about how caste plays a role in high school. And in the simplest terms, it has done much more harm than it has ever done good. And it will continue until we don’t take a strong stance of where we stand with this.

My caste does not define me, and though it might stick with me for the rest of my life, I know who I am and what I believe in. Not disclosing my caste makes people uneasy, they cannot label me and that’s what is powerful about you, it’s your voice, it’s your ability to disturb normality and question what people would normally indulge in blindly.

If you’re reading this, please question your core beliefs and ask yourself – who you are?

Finding your inner self is more crucial than what other people would like you to be and do.