Guest blog and research by Caitlin Garfias-Chan

Supervised by Marcella LaFever, Associate Professor CMNS

Ever wish you could change something where you live but feel like nobody would listen anyway? Deliberative democratic theory has caught the attention of many public officials interested in improving their communities and the last 15 years in British Columbia has seen growth in municipalities creating processes for public participation and deliberation for community planning. Often, the entry point for participation in such initiatives is through municipal online portals. The two questions for this current research project were to investigate: 1) extent; and 2) ease of access for participation processes throughout British Columbia.

Research by Knobloch, Gastil, Reedy, and Walsh (2013) define success in participatory processes as including analytic rigor (ensuring that decisions are based in facts and weighing all options; democratic discussion (ensuring that participants and process are relevant for the full diversity of the population); and well-reasoned decision (processing information from the, often conflicting, values and viewpoints of all affected parties). They also created a framework that defined and operationalizing six components: the context of the event, project design and setup, structural design, the discussion itself, experiences of the participants, and the output or product created.

Research by Knobloch, Gastil, Reedy, and Walsh (2013) define success in participatory processes as including analytic rigor (ensuring that decisions are based in facts and weighing all options; democratic discussion (ensuring that participants and process are relevant for the full diversity of the population); and well-reasoned decision (processing information from the, often conflicting, values and viewpoints of all affected parties). They also created a framework that defined and operationalizing six components: the context of the event, project design and setup, structural design, the discussion itself, experiences of the participants, and the output or product created.

Online participatory processes being used as a part of the effort to increase the ways that residents can be part of democratic decision-making impacts especially on two of the measurable components of the framework outlines above, the context of the participatory event and in project design related to diversity of participants and the inclusion pf processes for intercultural communication (LaFever, 2009). We decided to start by quantifying the number of municipalities across British Columbia, whether they used online portals to invite public participation and how easy those links were to find.

Method

The first step in determining our sample was to define how many municipalities would be included in our analysis. After finding a list of B.C. municipalities we decided to include cities, towns, districts and district municipalities with a population of 10,000 or more (as per the 2016 census). The list included 91 entities for analysis. We note here also that the list did not include First Nation communities.

Next was finding the data necessary and creating the criteria based on analysis. Using a spreadsheet, links to websites were used; both home pages and any engagement sites had dedicated spaces. At the same time, screenshots were used to emphasize further and provide proof of any possible engagement. The criteria are based on the opportunities given and how easy it is to find those same opportunities. It was noted that while some have an abundance of engagement projects, it was sometimes difficult to find them due to the website layout.

Next was finding the data necessary and creating the criteria based on analysis. Using a spreadsheet, links to websites were used; both home pages and any engagement sites had dedicated spaces. At the same time, screenshots were used to emphasize further and provide proof of any possible engagement. The criteria are based on the opportunities given and how easy it is to find those same opportunities. It was noted that while some have an abundance of engagement projects, it was sometimes difficult to find them due to the website layout.

Findings

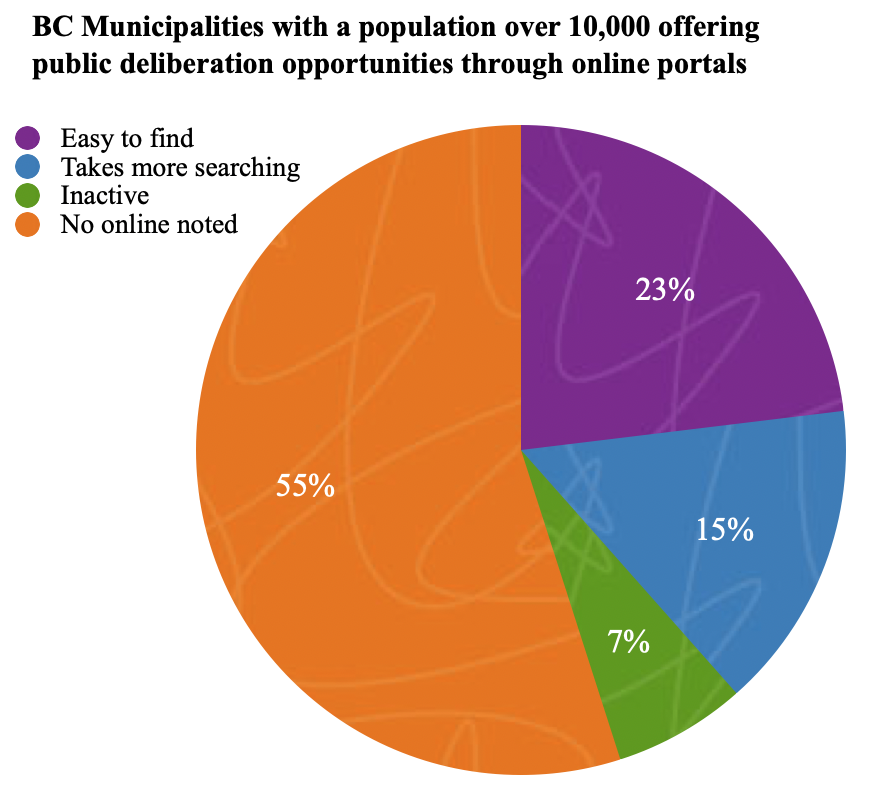

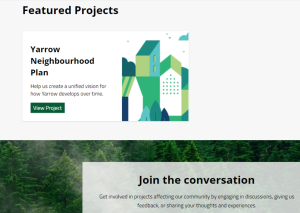

Data shows that out of 91 municipalities, 35 have ongoing/active public engagement opportunities noted in their online presence (surveys, meeting the mayor events, engagement websites). These included municipality sizes from as large as Vancouver at a population of 631,486; to medium sized such as both Abbotsford and Chilliwack; to the smaller sized Mission at 38, 833 and places like Fernie and Creston with just over 5,000 population. Out of the 35 municipalities, 21 had their engagement tabs accessible in obvious ways at the top of the page and with wording that was directed at residents. And with very few clicks to get to a link that noted online public engagement opportunities. 14 had engagement sites that required a search through several “community” tabs or at the bottom of their homepage in small print.

On the other hand, the majority, 50 municipalities, have no public engagement opportunities listed or only in ways not related to this research (i.e. speaking at council meeting). The additional six municipalities had some engagement in the past but had been inactive for several years, and of these only three have an easy-to-find archive page of those initiatives.

Of 91 BC municipalities, only 38% are actively promoting projects and thus promoting public engagement within their communities. And only 60% of those municipalities are easily accessible through their website.

Conclusion

As a first step this analysis was essential to a larger project to look at whether online portals are effective in increasing overall public participation in deliberation related to community planning. However, there are many gaps that can only be answered through a more in-depth look at specific projects across a spectrum of these communities. There are both smaller and larger communities that have online portals which will be an aspect to investigate in the next stage of the research, asking if there are significant differences in the various measurable components. The biggest issue may be determining whether the resultant deliberation events ensure that both participants and process are relevant for the full diversity of the population.

References and additional resources

Knobloch,K. R., Gastil, J., Reedy, J. and Walsh, K. C. (2013) Did they deliberate: Applying an evaluative model of democratic deliberation to the Oregon Citizens’Initiative Review. In Journal of Applied Communication Research 41(2).105-125

LaFever, M. (2009). 9P Planning. Overcoming Roadblocks to Collaboration in Intercultural Community Contexts. Proceedings: International Workshop on Intercultural Collaboration (IWIC). International Conference; Stanford University, Palo Alto, CA. Retrieved from https://www.researchgate.net/publication/247927917_9P_planning_Overcoming_roadblocks_to_collaboration_in_intercultural_community_contexts