As part of CHASI’s ongoing series on the current realities of life in Afghanistan under Taliban rule, we are honoured to welcome Fatema D. Ahmadi to the CHASIcast.

Ahmadi is a Fellow and Adjunct Professor at American University, School of Public Affairs in Washington, DC, and is dedicated to advocating for human rights, particularly women’s rights, in Afghanistan. Through her work, Ahmadi aims to spotlight the difficulties faced by vulnerable groups, gather data on human rights abuses, and advocate for transformative change.

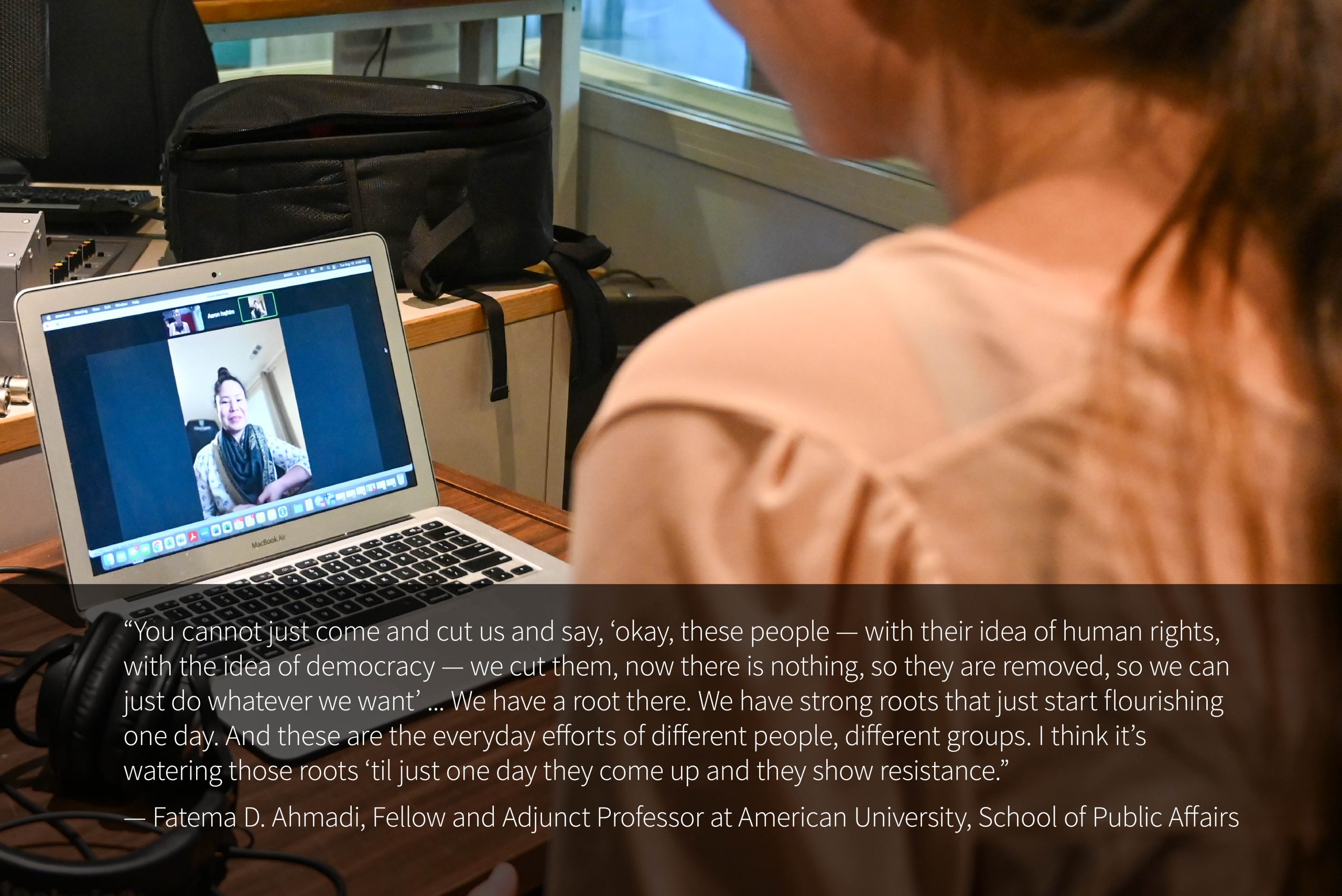

In this episode, Ahmadi joins guest host and CHASI Lead Researcher Chelsea Klassen to discuss growing up and pursuing an education as a refugee, the restrictive laws Afghan women are subjected to, and how people in Afghanistan and around the world are pushing back.

Recorded in CIVL Radio’s studio at the University of the Fraser Valley, the CHASIcast is available to stream below, or on Spotify, Apple Podcasts, YouTube, Google Podcasts, Amazon Music/Audible, and other platforms!

Powered by RedCircle

Transcript

Fatema Ahmadi: You cannot just come and cut us and say, “okay, these people — with their idea of human rights, with the idea of democracy — we cut them, now there is nothing, so they are removed, so we can just do whatever we want” … We have a root there. We have strong roots that just start flourishing one day. And these are the everyday efforts of different people, different groups. I think it’s watering those roots ’til just one day they come up and they show resistance.

Intro: Based out of the University of the Fraser Valley on unceded, traditional lands of the Stó:lō people, we are the Community Health and Social Innovation Hub, or CHASI for short. We support the social, mental, emotional, physical, and economic health of those living in our communities by bringing together experts from across disciplines. Those experts have some incredible stories and insights. To share those with the communities we serve, we bring you the CHASIcast, a monthly program where we drill down on a current topic and chat about how it impacts our lives.

Chelsea Klassen: So, my name is Chelsea Klassen and I am the lead researcher at the Community Health and Social Innovation Hub, and you’re listening to the CHASIcast today. Today we’re joined by Fatema Ahmadi. She is one of my dear friends and a fierce advocate for women’s rights in Afghanistan, as well as a peace builder in that country, too. Fatema, would you like to introduce yourself today?

Fatema Ahmadi: Yeah, thank you very much Chelsea and the team there for having me today for your program. I feel so honoured to be part of this podcast. As you introduced, I’m Fatema Ahmadi and I’m from Afghanistan. Right now I’m an adjunct professor and also fellow with American University School of Public Affairs.

Chelsea Klassen: Well, thank you for joining us today. When we’re, when we’re taping the podcast, it’s August 15th, 2023, two years since the Taliban took over Afghanistan. And Fatema I just want to give you the opportunity since it is, you know, this anniversary, what would you like people to know about that day?

Fatema Ahmadi: Well, as many of our friends of Afghanistan could imagine and people who were in inside of Afghanistan. It was a very sad and difficult moment to handle for all of us because it was unexpected and very unplanned and we were so hopeful for changes in [the] country after, you know, like 20 years of investment, 20 years of you know, people coming to the country from neighbouring countries and just being part of the community is that we build together and just seeing, with a blink of eyes, it was just going away and you’re there to see it. And it was really hard, really painful, to see all of that happening in front of your eyes, and you cannot do anything. And that day what I did, I just because I knew many of my friends, international friends, will leave, and I needed to say goodbye to them.

I went to, visited many of them, and, and just it was a hard day. Very sad. Well, every time I remember how I passed the day, I’m like, how I even now alive after just going through that difficult time. But we had a lot of cuddlings. We had a lot of cries that they… we were not expecting to see that for Afghanistan.

So, yeah, it was hard and still. It’s very hard alongside the hope that we have for the country because of this young generation that they really want to see a different peaceful Afghanistan and want to see their people living there with dignity in peaceful life.

Chelsea Klassen: I know the work that you were doing before you had to leave was around peace building. So maybe, would you mind sharing a little bit about the work that you were doing before you had to leave, around peace building?

Fatema Ahmadi: Yeah, my experience growing up in the region, layered with the conflicts, instability, and extremism, and all these concepts of difficulties. Yet, my interaction showed me resilience, a resilient individual that is striving for peace and for different country and community for themselves and for the people who are living there.

And it actually influenced my commitment to peace building a lot. And my personal experience and professional endeavors just highlighted the significance of conversation, dialogues, and comprehending each other’s sorrow and suffering, because I believe throughout the history of Afghanistan, each person, part of the community, experience so many painful events in Afghanistan. And if we talk about different range of unjust in Afghanistan, we can mention about Hazara genocide in late 18th century that just continued this ongoing and systematic ethnic cleansing under the previous regime and also under this Taliban that’s still happening with different reasons.

And It’s very important to understand that even with that horrible experience, we have other communities in Afghanistan that also last 20 years, for example, we saw that attacks happen to government institution, to hospitals, to education centers and different places that people should feel secure to be there.

But it was not secure for anyone to be in those places. And these experiences actually really changed the Afghanistan situation. And I believe that even that now that some people claim that’s Afghanistan is peaceful, I believe it’s not because we don’t have that life [where] everyone feels they are part of this community. They feel safe to be there. They are included in this society.

So, what actually what we have done in Afghanistan, you know, before this transfer of power in August 2021, we were hoping to engage more voices with peace building to find ways, how, for example, how we can find community led solutions for conflicts for each community because different regions and zones in Afghanistan, they have different problems and conflicts. So we had provincial dialogues, we had women’s talk, we had different programs for different levels. Journalists, we have, you know, international organizations who you know, work with us as a partner to, to train people, for example, in, in war and peace journalism.

And how negotiation, for example, for women who were part of the negotiation table. And it was mainly our first mainly focused on bottom-up peace building because it’s important that people in communities understand why we need to work together for peace. And building that fundamental understanding was the start of our work.

And by just adopting this foundation I think we can establish a framework for just understanding each other and also it is important, imperative that we remove all of this obstacles in front of us to understand that the big goal and the big problems and that ideology shouldn’t be in Afghanistan and should be removed from the society so we can see Afghanistan flourishing, and it’s not only [an] issue within Afghanistan.

It’s a broader regional issue. It’s a global issue because it’s not… the harmful practices that they just implementing right now in Afghanistan isn’t going to stay there and it’s expanding globally. And that’s why I think peace building, and then approach for peace building Afghanistan, should be continued and not as a project, not as a program to implement for a small endeavour and then finish it and, and then go for another one.

I believe it should be a very comprehensive way to just first making that pillar. And make the people to just see that peaceful vision and peaceful society for themselves.

Chelsea Klassen: Yeah, that’s really good, Fatema, thanks for sharing that. What experiences in your life — you talked a little bit about your experiences regionally — what experiences in your life have shaped your perspective on working in peace and conflict in Afghanistan?

Fatema Ahmadi: Well, that is a very interesting question. Well, I was a refugee and the whole childhood of myself passed as a refugee. I didn’t have a status because of this conflict. My entire family and my relatives had to leave Afghanistan during different conflicts related to different groups.

And because of living as a refugee in other countries, I had difficult time to even shape that identity. And as a person from Afghanistan, when I returned to Afghanistan. I just saw that I can feel that I’m part of this society. I can find a place to just inject myself, I find a smaller spot for myself.

I practice what I learned from my family, from my relatives and from my past and just be myself and just show it to just to the community easily and freely openly and say, okay, this is, this is a woman from Hazara ethnic tribe, for example. And this is educated woman who returned to Afghanistan.

But what I was feeling that missed so much in Afghanistan and lacked for many, many years, it was that when I leave my home, when I leave my office, I feel that I’m reaching to another destination, not being, being attacked by insurgent groups. So that feeling stayed with me for a while.

And then I, when I work with an organization called Hagar International on helping disadvantaged groups, especially women and children. And I see every day, not just experiencing myself because of discomfort from being a refugee. I saw people have to go through so many hard experiences because of this conflict. We didn’t have the proper system of protection for children. We didn’t have a proper system of protecting women. And minorities, and groups, vulnerable groups, like, for example, old people.

So, all of these categories showed me how this conflict is impacting and influencing daily life of all people in Afghanistan. So that’s why it pushed me more to see that peace building is important and I need to join this this effort in Afghanistan. And when I decided to join the USIP office, I just seeing that women’s voices are not heard, women are not part of the negotiation, and I personally, I’m so dedicated to women’s rights, and I saw that we should be, you know, we should push harder for including women, so that’s why I just started that part of my life after doing other activities.

Chelsea Klassen: So you touched on different groups of people being impacted by conflict in different ways, and that’s not a phenomenon unique to Afghanistan, that does happen in other countries that are facing conflict as well, but one of the unique parts of the conflict in Afghanistan, and particularly with the recent Taliban takeover is the issue of women’s education and the Taliban’s ban on women at university and girls older than grade three attending school. So I wonder if you might be able to tell our listeners a little bit about the challenges that women are facing in Afghanistan now, given the Taliban regime and how you’ve heard that has impacted their lives.

Fatema Ahmadi: Yeah, sure. You know, the ban on education is very personally also touching my heart because I still believe in profound, transformative kind of power of education for women because in countries like Afghanistan, women have access to limited opportunities and resources, and it’s very important to have that education and I’ve witnessed firsthand the life altering impact of education for my life because I mentioned earlier, I lived as a refugee and I just, every day I was singled out from the classmate, from class to stay home because “there is no confirmation for you as a refugee just to come and study.”

And it happened until I got my 12th grade, finished that. And it just, it was hard to manage that situation because I was not sure tomorrow I can continue studying or not, and during those years without a proper education or proper understanding of the system, education system, many of the students that were from Afghanistan, from fellow students were studying with me, they forced into early marriages and it actually stopped them from educational aspirations.

And this number of challenges just went with me until university. And even before university, I had the same experience because first, we were not allowed to go to universities because of that refugee status. Second, they, in some years, they were opening some small doors for refugees to do the exam and then they were saying, “Oh, you should have to pay three times more” or, you know,” refugees have to pay this amount.” And I didn’t have that money. My family didn’t have that money. So, I had to sew shoes for many months to just collect that money.

And I just understand how, when I mentioned earlier about my fellow students from Afghanistan that got married, I see that impact in Afghanistan right now because… and I talked to some of the girls that I knew before you know, this situation. Many of them, they got married because there’s no hope for them to see a change, or [that] tomorrow they can go to school under this Taliban regime.

And it’s not a perfect situation. It’s really, when I see from different angles, is this Taliban are systematically discriminating women and systematically depriving women from education and from other opportunities. You just asked earlier. How is this situation for women?

It’s not promising. It’s not a situation that other women in other parts of the world face and we just have okay, like some solution that work in other part of the world so we can implement it here. This is completely a new phenomenon that we just faced in Afghanistan.

And what we see every day, they’re just putting a new limitation on women and they’re just diminishing all of the public spheres on women and diminishing all of the opportunities for women to socialize. And when they came to power, actually, they dismantled so many laws and abolished so many laws, for example, the law on eliminating violence against women or the Convention of Elimination of Discrimination against Women.

These are not only simple laws that, you know, we talk about because in previous government, where women and the civil society tries so hard to just bring all of these changes in Afghanistan because of these laws and the, you know, when institutions like Ministry of Women’s Affairs, we brought some sort of protection for women in Afghanistan.

And right now there’s no protective system. And they dismantle all of these laws, policies, and, they [are] just replaced with limitations. As of June 2023, they have released more than 60 decrees and directives to just hinder women from public life, which, when we talk here it seems so silly, but it’s just everyday life in Afghanistan. I’m just telling you some of them and we have, I mentioned, more than 60. They’re just going to very personal aspects of woman’s life in Afghanistan. And they think how they can just put another limitation for women and feel better for themselves.

On August 25, 2021, when they came to power, they said, women [will] stay home for safety reason. And they mentioned our soldiers are not, prepared to see women in public life, spheres. And then they, in December 2021, they stopped women from traveling more than 45 miles without a male relative. December 20, they just completely banned women from education, attending actually public and private universities. And in the December last year, they stopped women from working with NGOs and they didn’t stop there actually, they’ve gone far beyond that. And they impose the bans on sectors such as bakeries, medical centres, beauty salons, and small businesses.

And it’s impacting not only the daily life of women because it’s a direct impact for women’s not having some of the financial stability and financial capacity to buy stuff and to just pay for the life that they want. It’s also impacting the economy of the country, more than 40% loss for the GDP growth in Afghanistan happened after this ban.

And it’s going beyond that. You know, when we think about Afghanistan economy, it’s just dropping, and it’s continued because women are part of this society. They should be part of the economy and also the part of this workforce I mentioned earlier, it’s a new, it’s a new ideology I would say, that Afghanistan, and specifically women in Afghanistan, are just fighting every day with that and with different ways they are trying to show to the world that we exist and they should hear them.

Chelsea Klassen: Yeah, my follow up question, Fatema was how are women resisting?

Fatema Ahmadi: Well, you know, maybe some of the listeners heard about groups in Afghanistan that after the collapse, they came to the streets, they marched, you know, in different streets of Kabul and some of the provinces, and they demanded, they demanded political participation, women’s rights, and their presence in society and also in government.

Which are, in my view, are powerful messages to the world and to the people of Afghanistan that women right now in Afghanistan understand their rights and they know what they want and they’re fighting for it. So, how they’re resisting. We had different coalition, you know, movements that they have shaped after August 2021.

And right now, because of the crackdown of the Taliban on women protesters, they just had to leave the country. They came to other neighbouring countries, but they have now [a] coalition, coalition of women’s protesters that is still trying to unite women together and to coordinate movements, coordinate coalitions, coordinate groups inside of Afghanistan and also outside of Afghanistan, to just raise their voice even today they, the same coalition of women’s protestors they had a big demonstration in Islamabad, and they ‘re just clearly to the world it’s not possible to have a country without women. And also people outside the, you know, human rights defenders, women’s rights defenders, the activists outside of Afghanistan in exile, they’re not silent.

They go to universities, they talk to students there, they just go to events. And they, like me, they are doing podcasts and just telling the world that we are not silent. You know, we, they cannot remove a woman from there. From decision making. So I think altogether that you continue doing the work that we believe that bring changes in Afghanistan, and it’s coming from that hope that I’m just talking and mentioning a lot that we are not you know, we are not giving up, we are not forgetting that Afghanistan, it’s our country or it’s our land, we have roots there and they cannot remove us.

You cannot just come and cut us and say, “okay, these people with their idea of human rights, with idea of democracy, we cut them, now there is nothing, so they are removed, so we can just do whatever we want.” No, it’s not. We have a root there. We have strong roots that just start flourishing one day.

And these are the everyday efforts of different people, different groups. I think it’s watering those roots to, ’til just one day, they come up, they, and they show resistance.

Chelsea Klassen: That’s a really beautiful image of the watering of the roots. And yeah, I know so much of Afghan culture uses symbols and storytelling. And so I really appreciate that that image.

Just to wrap up, my final question would be, you know, many people will hear about what’s happening in Afghanistan. And even today, we had a walkout event, a rally at the university. And, you know, after our Afghan activists spoke, people were like, “but what can we do next?”

So how can people who are allies of Afghan women and allies of a free Afghanistan, how can we combat those human rights violations that are happening in Afghanistan?

Fatema Ahmadi: Right, I just want to emphasize a lot on the role of allies for a free Afghanistan, because we are together and we should not give up together for that country to be free of extremists, Taliban, and specifically here, I will mention about Canadians’ role because I feel like they are playing a pivotal role in supporting Afghan women and Afghanistan, but specifically, they can raise awareness about what is happening in Afghanistan, the human rights violations, and the struggles of Afghan women and Afghan people and amplifying voices of people of Afghanistan and their demands. You know they have different demands of the Taliban and people who are inside and advocating for the policies that prioritize human rights on the top of the decisions, because when we think about other countries, we believe that, okay, based on the democratic values and based on human rights, what are the best approaches to take.

And for Afghanistan, it’s the same, because those are the people who are living there. They are people, they are humans, and they are individuals with, you know, with understanding of their rights. And they want to see that the policymakers and decision makers considering when they are making decisions, or they go and engage with this Taliban. Human rights, and also democracy. These are the values that are so important for our people.

And specifically about Canada, I’d say it’s a country with a feminist foreign policy, and they need to emphasize on policy to advance gender equality and empowering women and girls in Afghanistan. And they can do it either by pushing the Taliban’s request for recognition or advocating on behalf of African women and girls or Afghan people in international stages.

You know, sometimes we are not there. We don’t have a representative and when the other representative of Canada or other countries are there, they should consider we actually want them to think about their policymaking and decision making, because they say, you know, our values are based on human rights or, [feminism is] part of our foreign policy.

And finally, I think fostering partnership with organizations which are dedicated to education, healthcare, and empowerment actually can be a tangible difference, but not only including women as beneficiaries but also women as implementers and women who are leading these efforts in country and also outside of country.

Sometimes if some foreigners [are] coming together to for example, to help Afghanistan, that is so valuable, that is so important to do it. But take advice from Afghan people and also from [people] who have worked with Afghanistan for many years, and know the reality on the ground.

They have roots, they have networks, and they can help them for better implementation and to avoid discrimination, for example, in programs and reaching all of these vulnerable groups, religious minority groups, and in Afghanistan, who are under restriction and also not benefiting from the internationals aids in Afghanistan.

Chelsea Klassen: Well, thank you so much for taking the time to speak with us, Fatema, I could talk to you for hours and we have had long conversations before, but thanks for taking the time to share, just a small snippet of what we could have talked about around Afghanistan and telling us from your perspective and sharing some of your personal stories about why it’s so important to engage and be allies and support Afghan women. So thank you so much.

Fatema Ahmadi: Yeah, I would appreciate your time and also your attention around the issues related to Afghanistan and be very supportive for my people and also for my country. Thank you very much for your time as well.