What do group decision making, professional human guinea pigs, natural disasters, and scientific misconduct have in common? These were the topics that stood out to me at the Canadian Association of Research Ethics Boards 2013 National Conference: Fifty Shades of Research Ethics.

Presenters on these topics spoke passionately about the role of communication and language practices that can help or hinder researchers from conducting research in ethical ways.

Making decisions is complicated

Ivor Prichard from the US Department of Health has conducted research investigating why different Research Ethics Boards (REBs) respond differently when presented with identical research ethics applications.

Drawing on Barry Schwartz’s work from the book, The Paradox of Choice, Ivor highlighted some of the communication-related factors that may influence these different decisions.

“REB members, like all humans, tend to make decisions based on loss aversion,” he said.

“When people are faced with situations that are framed in how many people will survive, they are less likely to make a decision involving increased risk. But when situations are framed in terms of the number of deaths that could occur, people are more likely to accept increased risk.”

Ivor also found that words like ‘should’ and ‘shall’ in review guidelines invoked the desire for more deliberation in some REB members, in comparison to words that reflected ‘reasonableness’ or ‘a favourable balance’ of benefits and risks.

REB members can also influence each others’ decisions through processes such as reciprocation.

“If I agree with you now, you might feel obliged to return the favour and agree with me later on,” he said.

“Social proof, also known as ‘monkey see monkey do’ influences decisions. You can see this mimicry in practice when you watch street crossing behaviour. One person goes and the rest follow, even though a light may not be green.”

Ivor also discussed the human tendency for people to defer to authority and agree with people they like (or like the look of) as issues for REBs to be aware of.

Selling their bodies for science

Roberto Abadie, author of The Professional Guinea Pig spent years tracking people who make their living as volunteers for human drug trials in the United States. He found that these ‘professional human guinea pigs’ could earn a good living by ‘selling their bodies’ in clinical drug trials in comparison to what they could earn in other professions available to them.

“The financial benefits outweigh most of the perceptions of risks for these professional guinea pigs,” said Roberto.

He found that some of the professional volunteers saw the Ethics Consent Form for these trials as their job contract, rather than an informative document (describing the risks and benefits for participating in the research).

“Once it [consent form] was signed, they [volunteers] would be paid to work in the study. They would essentially know their job conditions.”

Roberto also found that some of the professional guinea pigs saw the consent form as a hurdle to jump. The form described the expectations of the researchers in relation to the participants as well as the risks but once it was signed, participants could forget about it.

These attitudes to Participant Consent Forms were a surprise to me. Participants need to be fully informed about the risks and benefits of a study to give truly informed consent. But if large sums of money are involved then this seems to override almost all other considerations. I was so impressed by this talk that I bought a copy of Roberto’s book (just published by Duke University Press).

Putting the community first

Anna Pujaidas Botey from the Alberta Centre for Child, Family and Community Research spoke about research she was involved in after the Slave Lake Fires in 2011. She and her collaborators visited the Slave Lake community in August 2011, only three months after one third of the town was destroyed by fire.

The team were interested in researching community resilience and rebuilding after the event, but received some initial resistance from a Slave Lake Council member to conducting the research.

“We spent a few weeks in the community, talking to people and working with Councillors and Emergency Planning staff, before starting to interview anyone,” she said.

“The needs and priorities of these affected communities have to come first in this research. Without direct benefit to them [community], it [the research] is not ethically sound.”

Anna and the team also invested research funds into making sure that the findings of the study would contribute to future emergency planning in the community—and involved those who would be most affected.

The group gave public presentations, wrote pieces for the local paper and other media outlets and posted the study findings on a website.

Retracting science

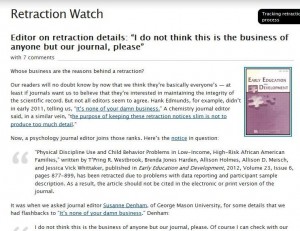

Adam Marcus, a journalist and cofounder of Retraction Watch, has been tracking scientific misconduct since 2010. He said he started the site with Ivan Oransky, MD as a way to give people a widow into the scientific process.

“Science takes pride in self correcting but it has no process for talking about that when it comes to the demise of a paper,” said Adam.

Adam and Ivan decided to create a blog rather than a print publication on retractions because they thought the blog was “more nimble”, less expensive, and more transparent.

Contrary to what researchers have believed, the majority of research paper retractions are due to misconduct rather than mistakes. Adam supplied examples of researcher misconduct ranging from plagiarism and falsifying images to poor graduate student supervision and ‘losing’ data once a paper has been published. Some researchers made up research participants or ignored the need for ethics approval.

“Researchers are under enormous pressure to publish, but we all need to represent ourselves fairly and honestly to people who are actually paying us and supporting us,” said Adam.

Not everyone is pleased with what Retraction Watch is doing. Adam said he has encountered resistance from some journal editors when he has inquired into the nature of a retraction.

“Just because we are seeing a rise in retractions doesn’t mean science is crumbling,” he said.

“The numbers of retractions are still small compared to output. Scientists are human, with human desires. Perhaps we are looking more closely at this issue than we were in the past.”

Retraction Watch is read by scientists and policy makers but is also useful for Research Integrity Officers, funding bodies and REBs.

This is great stuff about research ethics Michelle – thanks for posting. I see a direct connection in the Stave Lake study to my work in community dialogue and decision making.