From Marcella LaFever and Shirley Hardman

It started off as a trip to help out a colleague who was having eye surgery in Albuquerque, New Mexico. In the end it became a journey of thinking about when, how and what Indigenous peoples in the United States when they tell their stories publicly.

For this past year I have been immersed in my sabbatical research on Indigenous storytelling as a communicative practice in public dialogue, in particular in relation to use of stories in submissions to the Cohen Commission Inquiry on the decline of Sockeye salmon in the Fraser River. When my co-researcher Shirley Hardman accepted my invitation to fly down and drive back with me on the return trip we quickly decided that we wanted to visit a couple of universities with strong Native American Studies programs and plan our route to visit Indigenous communities along the way.

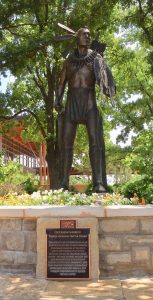

As we started our travels from Dallas/Ft.Worth Texas we headed just north to the state with the largest Native American population in the U.S., Oklahoma. Our main goal was to visit the University of Oklahoma but we also wanted to stop wherever we saw First Nation sites along the way. This ended up including roadside markers such as the story Chief Joseph (left), complexes such as the Chickasaw Cultural Center, Sulpher, Oklahoma, and interactive memorials such as the Standing Bear Monument in Ponca City. Each of these were channels for telling stories publicly. There are many other ways of course and I will touch on some of the others we experienced later in the blog.

As we started our travels from Dallas/Ft.Worth Texas we headed just north to the state with the largest Native American population in the U.S., Oklahoma. Our main goal was to visit the University of Oklahoma but we also wanted to stop wherever we saw First Nation sites along the way. This ended up including roadside markers such as the story Chief Joseph (left), complexes such as the Chickasaw Cultural Center, Sulpher, Oklahoma, and interactive memorials such as the Standing Bear Monument in Ponca City. Each of these were channels for telling stories publicly. There are many other ways of course and I will touch on some of the others we experienced later in the blog.

At the Standing Bear Park we were a bit wary as we drove through a major refinery to get there. Never mind that further research showed that some of the oil being refined comes through Keystone from the Alberta oil sands and that oil played no small part in the despicable policies that displaced these First Nations peoples for a second time; the first being when they were forced to locate to Oklahoma territory by the U.S. Government under the Indian Removal Act that resulted in what is called the Trail of Tears.

Nevertheless, the story and site we experienced when we arrived was well planned for those who wanted to be engaged. We were greeted in the five languages of the local First Nation peoples and led through an outdoor interactive site that led us clockwise through the lives of the Osage, Pawnee, Otoe-Missouria Kaw, Tonkawa and Ponca communities, ending with the nearly 7 meter (22 ft) high bronze of Standing Bear.

After hearing the story of Standing Bear and learning of the peoples of the area we ventured into the Museum and Education Center to see other ways the stories were told. Inside the circular architecture of the center each of the five nations had their own case to display whatever they wished and included such things as art works, current event mementos, and some heirlooms. The center also hosted traveling exhibits, a display featuring all the models and the sculptures submitted as proposed designs for the Standing Bear bronze, contemporary artwork and pottery for sale, as well as a good selection of books. Clyde Otipoby (Comanche) was the featured artist when we were there.

Before leaving Ponca City we made a visit to what turned out to be the local pawn shop that also advertise themselves as the “Premier Oklahoma Pow Wow Store.” (More about “beads and beading” as storytelling later.)

Soon after leaving Ponca City we made our way to the University of Oklahoma and the Native American Studies Program in Norman with the goal of finding out what American universities might be doing to indigenize their campuses. We spent a fantastic afternoon escaping the 30c heat and it was great to be in the university atmosphere. No one even blinked (although they did smile) at our traveling companion Rocky (#rockyrapido).

UO is a huge campus so we stopped in at Visitor Center where we were immediately made to feel welcome and introduced to Jarrod Tahsequah the Assistant Director of Diversity Enri

chment Programs. Jarrod (Comanche-Choctaw), Norman born and raised, got us excited about what was happening on campus, showed us how to get to Breanna Faris (Cheyenne-Arapaho), Assistant Director for American Indian Student Life, and from there to the office of Dr. Amanda Cobb-Greethan, the Chair of the Department. Amazing, everyone was on campus despite being after end of term. We were also impressed with such things as the elevator that was completely clad in a historical photographic mural of what we could only imagine was a local Indigenous community (no interpretation was provided). Both Jarrod and Amanda ensured we were OU American Indian bling equipped before we left campus – a definite plus to make us the envy of tribal members back home.

While doing our homework ahead of our visit we had found that it had been more than 100 years earlier that the department had been established and the promise of their own building made. While that goal has still not been achieved, Dr. Cobb-Greethan was quite happy to show us around the entire floor that they occupied. We were greeted by a guest book and map where visitors were encouraged to add their Nation identity and pin a map (the one created by Aaron Carapella). Amanda also explained to us that there are 39 tribal groups in Oklahoma and that each was represented by the flag of their Nation posted the length of the hall. She also pointed out that there was plenty of room for any student who came to the program from outside Oklahoma to bring a flag to post as well and that they were actively encouraged to.

The star quilt, which we saw over and over again on our tour, and which we carried home adorning our bling, has significant meaning at OU. The quilting, undertaken to produce these various stars, was learned in Indian boarding schools. There is an act of reclamation in using the quilting learned in those place of cultural dispossession and the “star” as it has become an accepted pan-Indian design, to create the star quilts today – this act termed by those at OU as a cultural sovereignty. These are a couple of ways that students can tell their stories in a public way.

After negotiating through some stories told and untold about Lewis and Clark interactions with the peoples they met on their trek along the Missouri River, we made our way to the University of South Dakota in Vermillion

Again we had a wonderful reception as we found our way around the University of South Dakota looking for Native Student Services and Native American Studies. First we met Donis Drappeau (Ihanktonwan Oyate) at the Native American Cultural Center that houses the student services and acts as a study and gathering place. We heard not only some of her story but stories of the center and successes of the students. The NACC was undergoing summer renovations and much of the furniture and aesthetics were shoved to one side to allow the reno workers access to the Centre. What remained on the walls were seven core-values (Humility, Generosity, Sacrifice, Fortitude, Compassion, Wisdom and Respect) translated into Lakota, Nakota, and Dakota. Donis then pointed us in the direction of Dr. Elise Boxer (Assiniboine – Oglala Sioux) , Coordinator of the Native American Studies program. Elise was very proud of the department’s direction in changing from one that focused on the past to one where classroom and research is rooted in the present and looking to the future. Dr. Boxer’s office was crowded with sewing machine boxes, when Shirley asked, Elise explained that the sewing machines are part of her community outreach.

From Vermillion we head due west across the plains though Sioux territories. Beadwork had brought us stories all along the way as we stopped in First Nation Communities. Shirley says the “raven” in her cannot resist shiny things and beadwork qualifies as shiny things. Anyone who knows Shirley know that she wears beautiful beadwork made for her by her niece Collete Williams, Skwah Band member. Many people will comment on the beadwork Shirley wears but it is only in First Nation communities where people bring stories to the conversation. For example when we stopped for the night at Rosebud we met the lovely Elsie Huber. Elsie explained that she had lived on the Rosebud reservation almost her whole life. She went on to explain that it is the best place on earth and that now more than 80 years since she was born she is rich with children, grand-children the land she loves and the dawning of each new day.

More stories came as we traveled through Wounded Knee, Pine Ridge, at the Crazy Horse Monument, the Little Bighorn Battlefield, and Head Smashed-In Buffalo Jump. So many of these stories ask of us a solemnity that the area demands. At Wounded Knee we offered tobacco, hiked the muddy road to the monument, spoke with hovering locals hoping to secure a few dollars to get them through one more day from the tourists who persist. It was a windy, cold day when we offered more tobacco at the Little Bighorn Battlefield, at a time of year just one month before the annual commemoration.