UFV researcher tackles toxic operating room cultures

Operating rooms are meant to save lives, but research by Dr. Alexander Villafranca, a faculty member at UFV’s Kinesiology department, suggests they can also be toxic workplaces. Now, he’s developing tools to help stop disruptive behaviour that can put both patients and staff at risk.

Studies led by Alexander show that bad behaviour is commonly directed at patients, who may hear disrespectful comments about their state of health or physical appearance. It’s also directed at colleagues, and he says the infractions range from mild incivility to egregious abuse, including physical altercations in the operating room (OR).

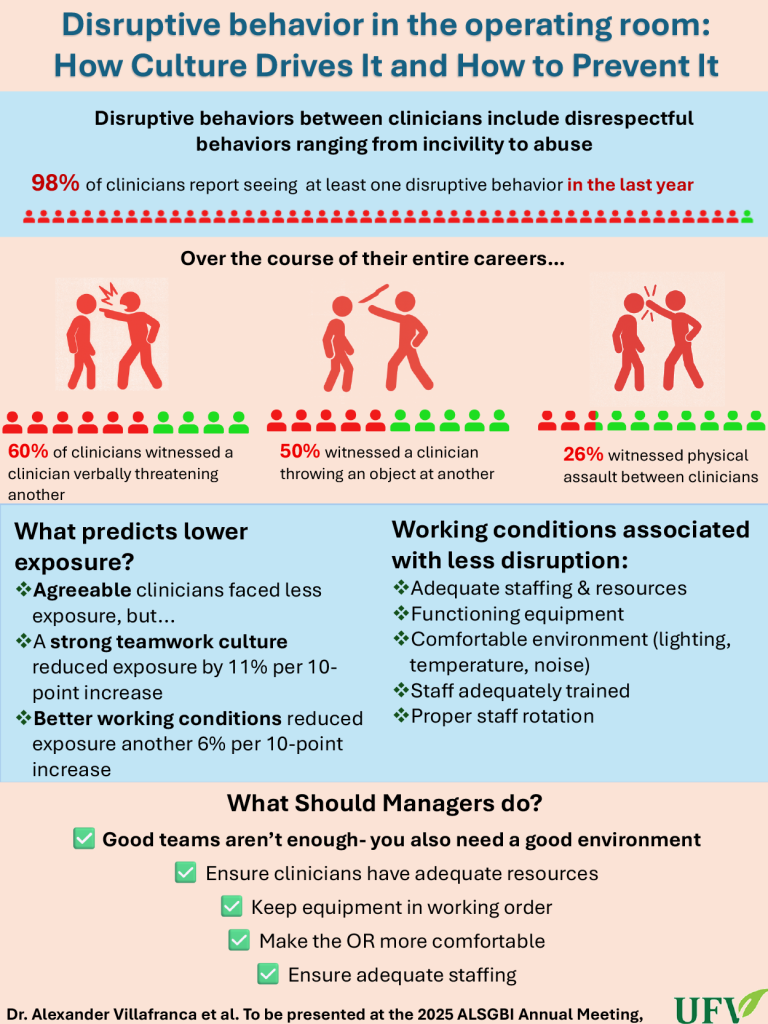

One project he led surveyed 7,500 clinicians across seven countries. Over the course of one year, 97 per cent were exposed to at least one incident of disruptive behaviour, and the average was about 60 events.

“When I tell that to laypeople, they’re shocked at the 97 per cent,” Alexander says. “But when I tell that to clinicians, they’re shocked that three per cent haven’t experienced something.”

Alexander has seen much of this firsthand. While pursuing a master’s degree at the University of Manitoba in 2010, and working as a research technician, he spent lots of time in operating rooms.

“I attended about 750 cardiac surgeries and saw firsthand a lot of interpersonal dynamics,” he recalls. “I saw incidents that I found a little bit shocking, and when I spoke to people, they suggested that it’s par for the course and medicine’s dirty secret.”

Since then, Alexander has spent years conducting research that brings the problems to light and offers solutions.

“This impacts patients because if you have people acting poorly, and other people responding to that disruption with more disruption, you’ve undermined teamwork, communication, and clinical judgement,” he explains. “It’s also undermining technical performance because people get nervous, and shaky-handed surgeons perform worse than non-shaky-handed surgeons.”

At a time when healthcare workers are getting harder to find, the toxicity also impacts the employers’ ability to hire and retain qualified individuals. As Alexander notes, people who are treated badly at work don’t want to go there. Attrition and absenteeism increase while organizational efficiency goes down.

“It really is a hair-on-fire problem,” he says.

Bringing the problem to light is one goal, but Alexander wants to do so in a solutions-focused way. He developed one survey tool to help quantify and monitor the problem, and another to determine how people respond to the behaviour.

“It’s not just one person acting badly, but that person is doing so while embedded in relationships with other people,” he explains. “The responses of other people can make it better or make it way worse. We want to eliminate the behaviour, but we also need to build in a safety net so that when it does happen, the wheels don’t come off.”

Part of the issue, Alexander says, is the environment in which clinicians work. People are crowded into a small space where they work long hours together with few breaks. Operating rooms are naturally high-stress environments, with extremely high stakes.

Alexander calls it the perfect storm.

“One of the things that we’ve set out to do is identify the working conditions that are most predictive of disruptive behavior,” he says. “For instance, if you are in a space that is very hot, loud and bright, that is a big predictor. If your tools aren’t working properly, that’s another one. We’re identifying those things and giving managers very practical things that they can do to reduce incidents. Small tweaks to an environment can have a big effect.”

Who engages in bad behaviour changes from place to place. Sometimes surgeons are the offenders, other times it’s nurses or anesthesiologists. Sometimes it’s a combination, and it’s almost never simple.

“You might be in a situation where a lot of this behaviour happens, but it’s due to one or two people, so you’ve just got a couple of bad apples,” he says. “The solution to that is potentially different from one addressing an environment where everybody does it all the time, because then you’re in a toxic culture.”

All of Alexander’s research depends on clinicians being forthright with their survey responses. While they may be willing to disclose incidents in an anonymous survey, doing so in the workplace is different. Fear of reprisal is a big reason to keep quiet, but Alexander believes people want to talk about it.

“There are clinicians who recognize how detrimental the behaviour is,” he says. “I cannot go to a conference without having a line of five or six people wanting to tell me their war stories, and I use those stories to inform the tools and questionnaires that I create.

“There are clinicians who are willing to confront it and study it and try to make systemic change, and those are the people I try to align myself with.”

To learn more about Alexander’s research, visit www.clinicalteamworklab.com.