UFV researcher developing AI cure for loneliness

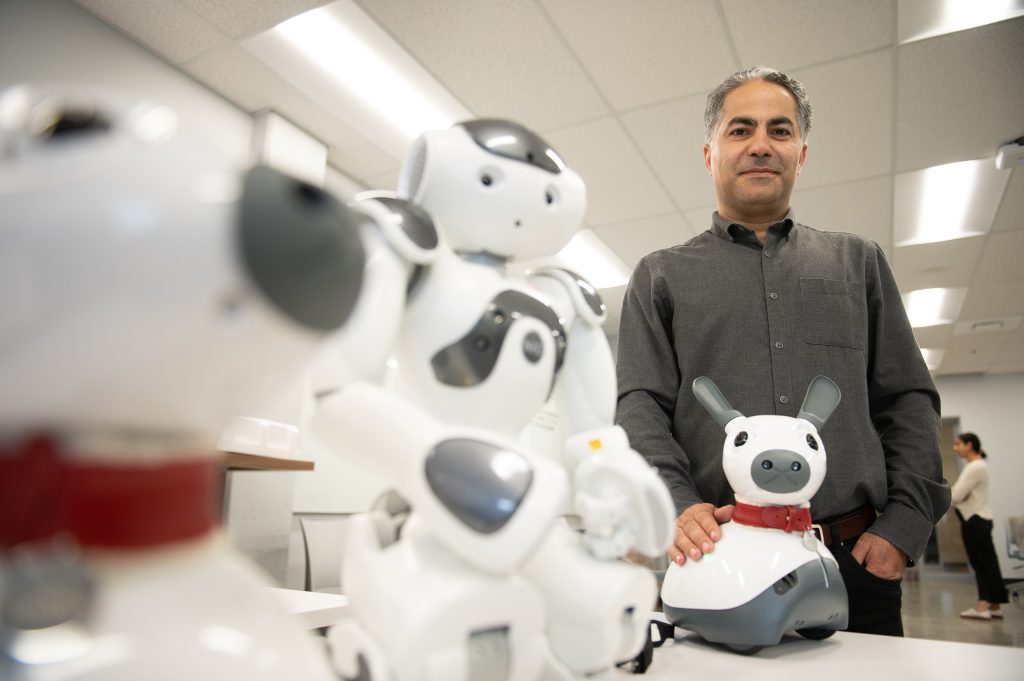

A UFV researcher is gaining national attention for his work with artificial intelligence (AI) and robots. Dr. Amir Shabani was recently highlighted in a MacLean’s article, talking about how robot companions with AI can be a potential cure for loneliness.

“Think of a digital pet that knows you and your preferences and is connected to the smart devices in your home,” Shabani explains. “It can turn on the heating or cooling, open the blinds, or whatever else you have. But it is a digital companion with emotional intelligence (EQ) with intention to more closely replicate the human-to-human interactions that we have.”

Before coming to UFV in 2019 and joining the university’s Community Health and Social Innovation (CHASI) Hub, Shabani was the National Sciences and Engineering Research Council of Canada’s Industrial Research Chair for Colleges and worked on applications of AI and data analytics for smart homes and smart-connected buildings. As he considered how AI devices could achieve energy optimization, he realized there was another route to take.

“We needed to also think about the comfort and wellbeing of occupants in their space and how we could address those things.”

Supported by a TD Ready Commitment for Better Health initiative grant, Shabani now collaborates with other CHASI researchers to investigate the role of AI and technologies in addressing loneliness in youth and elders.

The work Shabani and his research assistants are doing now could one day result in a small robotic bunny or puppy rolling around someone’s home equipped with a camera, speaker, microphone, and touch sensors – one that’s able to interpret and respond to human emotions.

“A lot of us feel lonely, and this is a technology that can address that,” he says.

Shabani points to Amazon Alexa, Siri and Google Assistant as software that listens and responds to specific commands, however a companion needs to be more emotionally sensitive for a more engaging conversation. Affective computing software is the key with its ability to recognize different emotions and deliver an appropriate response.

“The robot may say, ‘I feel you’re upset. Is that true? Is there any way I can help?’” Shabani notes. “Emotions are subjective, and they change from person to person, but over time it learns about its person’s typical requests or responses. It may know you like music and ask to play it because it knows music calms you down.”

As AI becomes mainstream, there are more big-picture concerns around privacy, ethics, and replacing the ‘human element.’ Shabani addresses these issues with a ‘human-in-the-loop’ and ‘human-centered’ design approach. This provides transparency and limits the robot from acting without approval from its person.

“Trust must be built whenever new technology is adopted because people are hesitant,” Shabani acknowledges.

For example, a connected companion robot may be able to monitor the news to know when a heat wave is coming and prompt its person to turn on air conditioning, close the blinds, or do something else to stay cool.

But not without approval from a human.

“Being in a smart home and connected to other systems, even though the robot could take actions, it does not,” Shabani says. “If its person remains unresponsive after several timely attempts, it may reach out to a trusted contact to say, ‘Your mom or dad didn’t turn on the AC, or the window is open. Would you like me to act?’”

Time moves fast and technology moves faster. In 2001-02, Shabani was working in robotics with industrial applications. Back then he could only dream of robot companions becoming this smart, and he says getting to this point is fascinating.

“Who’d have thought we’d have smart devices and robot vacuum cleaners adopted at this scale in our daily life?” Shabani says.

If a tech giant like Amazon or Google takes the leap into affective computing software and integrates it into their existing systems as a new feature, Shabani feels a practical application of his research could be as little as two or three years away for the public. For robot companions in the home, the wait may be longer. But maybe not as long as you’d think.

“It’s not far-fetched to imagine that within a few years we see significant movement,” Shabani says. “I’ve been in academic research for over 20 years and all that previous work is coming together now with this project. This is something I’m excited about because I see those 20 years being manifested in something quite meaningful, improving quality of life.”