Making history: innovative history course puts local stories from WW II online

A history paper seems like a lot of work, even from an outside perspective. The research alone is enough to make the most stalwart student stagger; add a couple dozen hours of compiling citations and leafing through library books that smell like the stone age, and a history paper is no small undertaking.

Even after the sources are tracked down, the books checked out of the library, and the newspaper clippings photocopied, it can seem like an almost insurmountable task to look at events of the past and organize them into some kind of cause and effect order.

And once that’s done, it seems almost absurd that the hefty stack of double-spaced pages — representing such a sheer amount of research, time, and effort — goes no farther than the professor’s desk.

This is why one history class at UFV changed the name of the game.

In the same way that books are evolving into e-books and journalists are diving into social media, history is moving into the digital era.

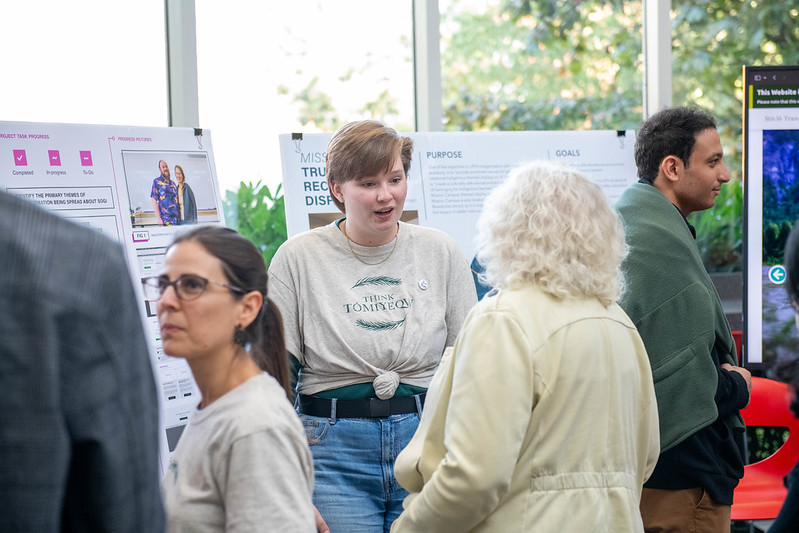

The idea is still in the fledgling phases, but two professors in UFV’s history department tested the waters of this new direction. Scott Sheffield and Robin Anderson joined forces to teach History 440: Local History for the Web.

The course allowed UFV students to explore the local history of their communities around the Fraser Valley, Sheffield explains. It also strengthened the bonds between UFV and Fraser Valley communities by preserving the events of the past.

But here the similarity to other history courses ends: instead of pouring their research into a final paper, the students enrolled in History 440 built websites to house their research — from scratch.

“We’d seen some, but very few examples of this kind of work in other history programs of students doing this research and turning it into something — not just research papers, but blogs and websites,” Anderson explains. “New media is really changing the face of the historical world — archives and museums, and the way we store things and study things.”

Over the course of several years, Sheffield and Anderson built the course around two objectives — combining the traditional element of research with web design.

It was this combination of new media and primary research that gave this course a spark.

“New media skills are becoming increasingly important after our students graduate,” Sheffield explains. “Employers in the history sector ask us to teach these skills alongside traditional skills — they’re becoming more and more in demand.”

A chance to develop web skills was one of two key elements the course offered to students; it also gave students an opportunity to try their hand at research of their own.

“It was neat for the students to feel like they were making history — not just reading other people’s take on it,” Sheffield says. “That’s what real historians do — work with primary sources and draw conclusions.”

Both professors felt that it was important to get the students out into the field; despite the fact that many were in the final year of their degrees, many of them hadn’t had the opportunity to explore archives or try their hand at primary research.

Depending on the topics they chose for their projects, the students drew directly from documents and other materials housed in municipal archives and historical societies around the Fraser Valley, spending hours at a time poring over materials and trying to understand events and social situations that are over half a century old.

“Municipal archives are eclectic creatures,” Sheffield says with a smile, “But in all the archives that we worked with, the students really found a wealth of resources.”

Because these are smaller local archives, the students were delving into history that hasn’t been explored in depth before.

“They looked at areas that haven’t seen a lot of study, and compiled high-quality historical information about the Fraser Valley,” Sheffield says. “They really constructed a rich resource, and filled a real void of information.”

Researching was fairly familiar ground to history students; the foray into the digital world was the real challenge.

Both professors felt it was important to build the websites from the ground up rather than plugging the information into a cookie-cutter design, but their plan to include web-building as an element of the course had one small flaw: neither Anderson nor Sheffield had any experience with website design or construction.

“Neither Robin or I are particularly tech-savvy,” Sheffield confesses. “We were basically a blank slate in terms of technology.”

This is where Marlene Murray, the History department assistant at the time, stepped in.

With a background in graphic design and experience putting together websites, she was perfect for the job. As the lab instructor for the course, she says that teaching the ins and outs of web design to 13 students and two professors wasn’t as much of a challenge as it may seem.

“The fact that the students had little to no experience was a blessing, because they were all on the same level,” Murray says with a laugh. “The main challenge was how quickly they had to learn, and how quickly they had to figure it out.”

There was apprehension on all sides, but Murray says she was able to snap them out of it right away.

“They were obviously concerned about whether they’d be able to do it, so on the first day I had them code a page in HTML,” she explains. “It was just three lines, and a single webpage, but it gave them an idea of what they were going to do and that they could do it.”

It was the combination of new media and traditional research that intrigued fourth-year history student Michael Schmidt and led him to register in the course. His website, which explored tensions in the Fraser Valley Mennonite community during World War II, won a UFV undergraduate research award.

“When I heard about the class I thought it would be a good challenge, and kind of different from the other history classes offered at UFV,” Schmidt explains. “It comes down to the fact that history can only flourish if you’re able to present academic research in an accessible way.”

Schmidt says he was drawn to the Mennonite community as a topic after hearing both his and his wife’s grandfathers talk about their experiences during the war.

“It really surprised me, because I was under the impression that all the Mennonites had were all conscientious objectors — that they refused to go to war with one voice,” Schmidt says. “But that simply wasn’t the case.”

As he dove into this conflict within the World War II era Mennonite community, Schmidt found himself branching into several different collections and archives to get the whole picture.

“Magazines and newspapers of the time weren’t too concerned with the religious conflict that was going on at the time, but there were some pretty heated town hall meetings out in Yarrow,” Schmidt explains. “It was mainly through Mennonite authors and Mennonite historians that I found my information.”

But digging up information was the easy part. Putting it into a website was another story.

“Robin assured us that no web design was needed, but getting into the computer lab for the first time was definitely a bit of a shock,” Schmidt says with a laugh. “But we were determined to give it our best. Historians are taking note that they can’t be so removed from the general public outside of academic circles. A popular history approach is available and is really what interests people.”

The idea of translating traditional research into other forms is one that this course really hoped to tackle, Anderson says. When nearly every university student has a smart phone and any school child can research a class project on the internet, it’s time for historians to start thinking about the evolution of their studies.

“How do we adapt our discipline to this new age and this new way of communicating?” Anderson says. “That’s the question we grapple with, and one that history, as a whole, is grappling with. But I think there is a good marriage there. You can have a piece that is academic, but still readable and adaptable. It tests and challenges the linearity of an essay, and tests our ability to adapt to this new media and still get our message across.”

The transition from paper to web wasn’t easy, and it challenged how students thought about the ways information can be presented. Paragraphs that would be linked together were instead split apart into separate sections that stood alone. Instead of a single block of text, students played with subtitles, visuals, and sidebars.

There was one surprising addition to these fun new elements, which somehow snuck in from the traditional form of history papers: footnotes.

Anderson, Sheffield, and Murray all viewed their inclusion with bemusement.

“Technically speaking, the footnotes were probably the worst of it — just trying to get them to work,” Murray sighs. “But after all, it was an element that was important to the students, to show that they were still part of the academic world, and that they’d done their research.”

And at the end of the term, when most classes were winding down for good, the students of History 440 watched their websites go live.

It was a moment that all involved took pride in.

“It was a challenging experience, but a beneficial one,” Schmidt explains. “When you challenge yourself and tackle things you think might be too much for you, you test yourself and you see what you’re made of and what you’re capable of.

“I think that’s what this experience was for me — opening myself to a new way of pursuing history — and it was an ultimately rewarding experience.”

This article is featured in the June 2013 issue of UFV Skookum magazine.