Rocky road: Getting university-college status for Fraser Valley College was no easy task

July 5, 2011 marked the 20-year anniversary of Fraser Valley College becoming the University College of the Fraser Valley, after a long and hard-fought community campaign. As there would be no UFV without there first having been a UCFV, serving as a transition from two-year college to university, we thought we’d share the history of how it came to be.

July 5, 2011 marked the 20-year anniversary of Fraser Valley College becoming the University College of the Fraser Valley, after a long and hard-fought community campaign. As there would be no UFV without there first having been a UCFV, serving as a transition from two-year college to university, we thought we’d share the history of how it came to be.

It’s possible to think of UFV’s journey from small community college to full-fledged regional university as a fait accompli, or destiny, but the road to university status was filled with stumbling blocks and barriers.

Perhaps the most crucial juncture was the transition to university-college status, which allowed the institution to begin offering third- and fourth-year programming, at first granting other universities’ degrees, and then eventually its own.

British Columbia first began experimenting with the university-college concept in 1989, when the new status was conferred upon Okanagan, Cariboo, and Malaspina colleges.

In March 1988, Stan Hagen, the Minister of Advanced Education and Job Training, announced the ‘Access for All’ initiative which would allow selected colleges to become university colleges, and in 1989 the government designated three community colleges as the first of this new breed of institution.

“Stan Hagen apparently went into a meeting having chosen Kamloops, Kelowna, and Prince George as the location of the new university colleges,” relates former FVC/UCFV president Peter Jones. “But Bruce Strachan, the MLA for Prince George, said no way, and that he would settle for nothing but a real university. So that’s where the University of Northern BC came from. The premier then asked Stan what community he would choose instead of Prince George, and he chose Nanaimo, because that’s where he was from. That’s how Okanagan, Cariboo, and Malaspina became the first university colleges. FVC was thought to be too close to the city.”

Folks at FVC wondered “What about us?” Even then the Fraser Valley was the fastest growing region for the demographic most likely to attend university. But politics have worked against FVC over the decades. When the conservative Social Credit government was in power, its members knew that the Fraser Valley seats were “safe”, so fewer rewards were necessary to keep taxpayers happy. When the NDP government was in charge from 1991 to 2001, they knew that there wasn’t much hope of winning seats in the upper Fraser Valley (apart from in Mission), so concentrated on areas where they were in contention. And when the Liberals came to power in 2001, once again the Fraser Valley ridings were considered “safe” so in less need of reward.

Still, there was a general recognition as the ’80s turned to the ’90s that something had to be done to increase access to education in the Fraser Valley. The Socreds commissioned former MLA Harvey Schroeder to conduct a formal consultation into access to post-secondary education in the area. He travelled the Fraser Valley, attending community forums and meeting with interested parties in the fall of 1990.

FVC saw an opportunity to push for the university-college status it had missed out on in 1989. Meetings were held, brochures published, briefs produced. Attendance at meetings was solid and support was good. FVC’s position was that it could become a university-college and there would still be room and sufficient demand for the creation of a new university further west in the valley in Surrey. Enthusiasm was high for moving to the next level in the Fraser Valley.

Then Schroeder’s report came out.

It recommended that a new free-standing university be built and operational somewhere in the Fraser Valley by 1995, and that Simon Fraser offer an extension program of upper-level courses in the Fraser Valley, perhaps by using Kwantlen and Fraser Valley College classrooms. It did not endorse the university-college model for which many Fraser Valley residents had vociferously lobbied.

Students, faculty, administrators, staff, and community members were all dismayed that FVC’s proposal to become UCFV was being overlooked and seemingly dismissed.

Sue Gadsby and Jaclyn Rea were two FVC students at the time, roommates and single mothers sharing a townhouse in Chilliwack while attending classes and raising their young sons. They had pinned their hopes on university-college status for FVC, knowing that it was the only way they and other students in their situation could afford to pursue a degree. They also loved FVC and its instructors and desperately wanted to continue their studies here.

“We’d been feeling pretty good about the prospect of getting UC status when the Schroeder commission was conducting meetings,” recalls Sue. “A lot of the community felt the way we did, that it was a ‘done deal’ that we’d get the status because community support was so strong.

“When the report came out without a strong endorsement of the concept, suddenly it was in jeopardy and seemed like it likely wouldn’t happen. We just decided that we weren’t going to take no for an answer. We wanted to ensure that the community was heard because it seemed that Schroeder hadn’t heard us the first time. So we created a community coalition to make it clear that Fraser Valley community members had a strong opinion about this. We wanted to show that it wasn’t just employees or even just students.”

“When we heard that the Fraser Valley wouldn’t be getting a university college, that really sparked the community,” recalls Bob Warick, who was director of community relations at FVC. “We knew that we couldn’t run a campaign entirely out of the college — the support had to come from the community. And the support was there. Individuals and businesses stepped up to buy ads to publicly support the cause.”

Fraser Valley communities, at least those in them with long memories, were used to having to apply pressure on government to get what they wanted when it came to higher education. It had taken over a decade and various false starts for the college itself to be legislated into existence.

The Fraser Valley rallied once again, thanks in no small measure to the Community Coalition to Support the University College Concept, run by Sue and Jaclyn out of their shared townhouse in Chilliwack.

Others were involved too. Pat McQueen was an eloquent FVC student from Abbotsford who was always willing to speak on the cause’s behalf. The FVC Student Society, at that time chaired by future Hope mayor Wilf Vicktor, helped organize large student rallies in Abbotsford and Chilliwack. And the FVC administration and the Faculty and Staff Association were strong and vocal proponents of the concept.

FVC’s Access committee (chaired by history instructor Jack Gaston), which had been tasked with finding a made-at-FVC solution to the access to education question and which had championed the university-college concept, met weekly to strategize.

FVC president Peter Jones and FVC board chair and noted horticulturalist Brian Minter were in constant contact with Victoria, letting the powers-that-be know that this issue wasn’t going to go away.

“Brian and I went to Victoria on several occasions to talk to Ministry of Advanced Education representatives and anyone else who would listen,” recalls Peter Jones. “Brian always brought flowers for the secretaries so that smoothed our way. Eventually, Advanced Education minister Bruce Strachan, who was very focused on developing the new university in his own Prince George riding, summoned us to a meeting. He was fed up with all the politicking going on in the Fraser Valley about this. He told us that we would not be getting university-college status and that there was no point in going further with our lobbying.

“Well, Strachan hadn’t encountered a community leader like Brian Minter before. Brian drew himself up purposefully and said in a polite but forceful way: ‘We will not be giving up on our quest. You’ll be hearing more from us.’ And he was right. The communities of the Fraser Valley refused to back down. ”

Letters were written and petitions were signed. The community coalition made presentations to city councils and civic organizations and did guest spots on local radio and were interviewed by print media. Community rallies were organized. As had been the case when lobbying for a community college was going on years earlier, community meetings were held in Chilliwack and Abbotsford.

“We got amazing attendance in Chilliwack,” Sue Gadsby recalls. “One man got up at that forum and said ‘when our kids go away to university they don’t come back’, and he made a passionate plea for making it possible for them to complete their degrees here.”

“The community really came through beautifully for us,” Peter Jones concurs. “Especially in Chilliwack.”

The two women leading the coalition led a frenzied life, balancing parenting duties, studies, and this impromptu community campaign. It was the days before email, Facebook, and the internet, so there were a lot of phone calls and letters and face-to-face meetings.

“We certainly racked up some huge phone bills,” Sue Gadsby remembers. “And the aviation students were prepared to fly us to Victoria for a meeting but that didn’t end up happening.”

It was an interesting time politically. The Social Credit party was coming to the end of a long reign. Premier Bill Vander Zalm had resigned amidst scandal and Rita Johnston, an MLA from Surrey, was now the premier. Local MLAs knew that their party’s chances of winning the next election were slim, so they were eager to get what they could for their communities while they still held the balance of power.

“This whole crazy campaign was going on during the dying days of the Social Credit government, but we were too deeply immersed in it to have much perspective on what that meant for our chances,” Sue Gadsby says. “It looked pretty bleak for a while. We heard that we’d been called naïve for even pursuing it by our own political science instructor, but we proved him wrong.”

The region’s MLAs weren’t super supportive of university-college status for FVC initially, former president Peter Jones recalls.

“We knew we needed to convince them that this was vitally necessary for the region but we weren’t having much success persuading them. So we brought in the former president of the University of Victoria, Howard Petch, who was quite a fan of the university-college concept. After Chilliwack MLA John Jansen met with him, he agreed to throw his weight behind the idea.”

There were several cabinet shuffles in the last months of the Social Credit government, and the stars seemed to finally align for Fraser Valley College’s ambitions when Chilliwack MLA John Jansen was appointed Minister of Finance and Central Fraser Valley MLA Peter Dueck was named Advanced Education Minister.

Many interpreted this as a signal that things were finally going to happen for Fraser Valley College, and that was the case.

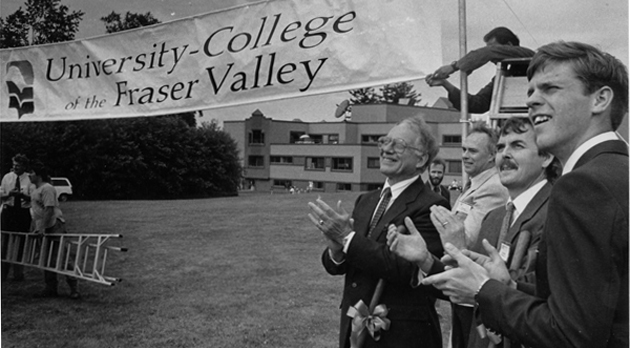

College officials were asked to prepare for a ceremony on July 3, 1991, on the Abbotsford campus. At that ceremony Peter Dueck announced university-college status for Fraser Valley College.

“We were so relieved,” recalls Sue Gadsby.

Although many people were involved in the campaign for university-college status, the two coalition leaders were recognized for kick-starting the campaign.

“I remember college board chair Brian Minter coming up to us with tears in his eyes, saying, ‘If it wasn’t for you two this would never have happened.’”

The front page of the Vancouver Sun the next day featured the two friends hugging and celebrating the victory.

This article is featured in the fall 2011 issue of UFV Skookum magazine