Appetite for food research took Lenore Newman on cross-Canada culinary quest

Dr. Lenore Newman has eaten her way across Canada. She and her appetite have traveled more than 40,000 km on a five-year quest to explore Canadian cuisine.

Dr. Lenore Newman has eaten her way across Canada. She and her appetite have traveled more than 40,000 km on a five-year quest to explore Canadian cuisine.

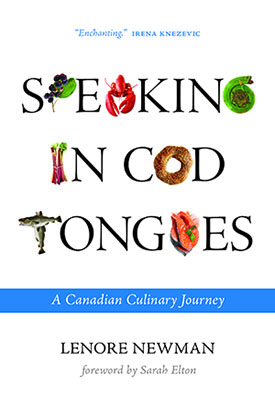

And in her new book, Speaking in Cod Tongues, Newman asserts that what makes Canadian food culture unique is our love of wild food like salmon and berries, our sustained respect for seasonality (such as waiting for fresh Chilliwack corn in July rather than buying California corn in March), and our enthusiasm for adapting and integrating foods from other countries into a Canadian Creole as we welcome immigrants from around the world.

There will be an official book launch for Speaking in Cod Tongues on Thurs, Jan 12 at 4 pm at the UBC Centre for Sustainable Food Systems as well as an event at UFV on Feb 21 as part of a faculty research celebration. Newman is also slated to be on CBC’s The Current. An excerpt will run in the Globe and Mail and it will be reviewed in the Toronto Star. You can buy the book on Amazon and in Vancouver bookstores.

Newman, who holds the Canada Research Chair in Food Security and the Environment at UFV and is a faculty member in Geography and the Environment, has focused her research on several aspects of food security, including the tensions between agriculture and suburban growth in “agriburban” areas such as the Fraser Valley.

Much of her time since joining UFV in 2011 has been devoted to researching the elusive Canadian cuisine, one piece of seal flipper pie or serving of poutine at a time.

You could say she has a real stomach for applied research.

Her journey took her on extensive culinary research tours through the Maritimes and Newfoundland, Quebec, the Prairies, and the Northwest Territories. She also researched British Columbia and Ontario, but as she had lived in both provinces for long stints she was able to rely on firsthand knowledge, with just a “refresher” visit to Ontario to see what has changed.

She was flooded out in Calgary and suffered an appendix attack on her way to a cranberry festival in Fort Langley, and regrets not getting to the Yukon or Nunavut. These gaps aside, she has probably eaten more regional dishes than any other Canadian.

Her culinary highlights included some “amazing” meals in Montreal but also eating a piece of rhubarb pie on a dock in New Brunswick.

Her culinary highlights included some “amazing” meals in Montreal but also eating a piece of rhubarb pie on a dock in New Brunswick.

“It was made by someone’s grandmother and it was not intrinsically the best pie ever, but it was good pie in good circumstances in good company. So much of what we remember and value about food is the context we eat it in.”

While seal and moose were not her favourite dishes, she recognized the importance of them to their regional economies and cultures and was grateful for the chance to experience them.

Across Canada, she was struck by Canadians’ continued enthusiasm for wild food.

“Every where I went, people wanted to share their locally sourced wild foods, from mushrooms to leeks to berries to game. I got to try herring roe on kelp in Haida Gwaii and Saskatoon berries on the prairies.”

She and her assistants, including post-doctoral scholars Denver Nixon and Lisa Powell and a “great group” of student researchers, supplemented the applied research with a survey of Canadian cookbooks over the decades, a review of the “sparse” academic writing on Canadian cuisine, and monitoring of food blogs and review sites like Yelp.

And her conclusion?

“Ours is almost a post-national cuisine. I call it the Canadian Creole. So many Canadian chefs are willing to do what the original Chinese-Canadian restaurants on the prairies had to do: mix the technique and recipes of their original cultures with the local Canadian ingredients. So we get halibut curry and blueberry lassi.

“It’s a reflection of our multicultural diversity and it continues to evolve. After welcoming the Vietnamese boat people we saw the development of Vietnamese restaurants. I suspect we will be seeing Syrian restaurants next, reflecting our latest influx of refugees.

“Our cuisine really reflects who we are as a people: welcoming and willing to integrate new ideas. As much of the world retreats into protectionist nationalism, it will be interesting to see what happens next in Canada.”

And Canadians value local, she notes. They wait with anticipation for strawberry season, then raspberries, blueberries, blackberries and peaches. A west coast meal of wild salmon, local potatoes and corn, topped off with a fresh berry crisp is quintessentially Canadian and has parallels in other parts of the country.

And Canadians value local, she notes. They wait with anticipation for strawberry season, then raspberries, blueberries, blackberries and peaches. A west coast meal of wild salmon, local potatoes and corn, topped off with a fresh berry crisp is quintessentially Canadian and has parallels in other parts of the country.

Newman was surprised by what an intense experience it was to traverse the whole country through several trips.

“Canada is so vast. If you really want to experience it beyond the big cities, to get to the more remote communities to find out what people are eating and thinking, you need to do a lot of driving. But it was a very Canadian experience. I’ve seen wolves, beaver, and even had a close encounter with a skunk.

”This research project was one of the most amazing experiences of my life and I am incredibly grateful for the opportunity that this Canada Research Chair at UFV has provided to me.”

Newman grew up the daughter of a fisherman on the Sunshine Coast of BC, and the Farmlands Trust operates her family’s century-old Newman farm on Vancouver Island.