Sto:lo Place Names tour brings indigenous history and landscape to life for UFV employees

How many times have you buzzed down Highway One from the interior to the lower mainland, focused only on getting home as soon as possible?

How many times have you buzzed down Highway One from the interior to the lower mainland, focused only on getting home as soon as possible?

You pass by the historic town of Yale in an instant, and in Hope you might stop for a snack, but not to linger.

The mountains and rivers are a beautiful blur as you zoom through at highway speed.

All the while, you are racing through a landscape full of stories, history, and significance to the Stó:lō people.

A mountain that is a woman, transformed to stone to watch over her people for all time. A waterfall that cries the tears of a grieving girl. A rockface where one family has fished since time immemorial. A wall of stones built to protect against invaders from the coast.

If you happen to go camping at Hope’s Telte Yet campground by the Fraser River and get site number 12, you’ll be right on top of Sonny McHalsie’s great-grandfather’s pit house, marked now only by a slight indentation in the landscape.

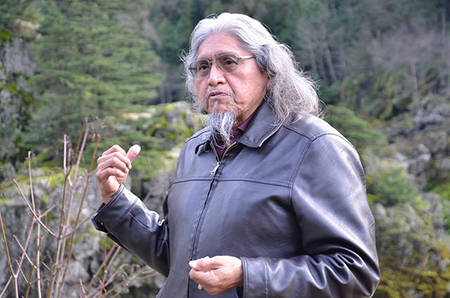

McHalsie (whose Sto:lo name is Naxaxalhts’i), the cultural advisor at the Stó:lō Research and Resource Management Centre, is also an adjunct professor of history at UFV who has been co-teaching the Indigenous Maps, Films, Rights and Land Claims certificate program for several years. He holds an honorary doctorate from the University of Victoria in recognition of his important work preserving the stories and culture of his people.

A group of UFV employees spent a professional development day on Naxaxalhts’i’s Stó:lō Place Names Tour on Nov 25, and the experience was the opposite of hurrying. The bus stopped five times at different spots along the way, and everyone trooped out to hear Naxaxalhts’i recount the stories of the surrounding forest, mountain, river, or lake, and their strong connection to the history of his people.

Enroute, Naxaxalhts’i took to the microphone as the bus rolled up the freeway, recounting almost non-stop the stories of every village, fishing spot, or hunting ground we passed. He shared place names and family names in rapid succession in Halq’eméylem, the language of the Stó:lō people, reciting from memory, failing to recall a word only twice in eight hours.

Naxaxalhts’i has led this tour for several UFV groups, part of the university’s commitment to the process of indigenization, and its acknowledgement that it is situated on S’ólh Téméxw, the unceded territory of the Stó:lō people.

Naxaxalhts’i has led this tour for several UFV groups, part of the university’s commitment to the process of indigenization, and its acknowledgement that it is situated on S’ólh Téméxw, the unceded territory of the Stó:lō people.

“It is very important that we be aware of our surroundings and this area’s strong connection to the Sto:lo people,” noted Ken Brealey, acting Associate Vice Provost, Faculty Relations, who was along for the tour along with most of UFV’s Human Resources department. “Driving through this area we are surrounded by culture, stories, and history, but it is not apparent at first glance. This tour with Sonny (Naxaxalhts’i), who is willing to share his extensive knowledge, helps to make the invisible, visible to us.”

Naxaxalhts’i said that connecting to the land and the stories it holds is a key part of reclaiming and reviving the culture of the Sto:lo people.

And he is playing a key role in keeping the oral history of the Stó:lō people alive after decades of colonization and cultural implosion. He has interviewed many dozens of Stó:lō elders in more than 30 years of work.

“The elders will say that the proof we have always been here is all around us, you just need to be ready to see it,” he noted.

Always during the tour, he acknowledged those who passed on those stories to him, ensuring that it is their and their ancestors’ memories that are preserved. As he noted “Our elders have always told us that we have to take care of everything that belongs to us.”

UFV employees on the Nov. 25 tour, including members of the Library, Teaching and Learning, University Relations, and other departments that joined Human Resources, described it as an eye-opening experience.

“I had the absolute privilege to be a part of the UFV tour of the ancestral lands of the Stó:lō First Nation between Chilliwack and Yale,” noted Mary Anne MacDougall, reference librarian. “Our tour guide Naxaxalhts’i (Sonny McHalsie) shared stories of the sacred and familiar places that are at the very heart of the people of the river. I learned so much and am so grateful to Sonny for opening my eyes and really seeing this land that means so much to us all. And I saw a mountain goat!”

“Getting to know the landscapes that surround where you live, work or play is something that can give you a sense of connectivity and ‘home’,” noted Maggi Davis, acting alumni relations coordinator. “Each rock, stream, hill or animal had a story to be told that shared the ways in which the people of this area treated the natural world with reverence and respect. Hearing how a warrior, or a mother, or a loyal dog was changed by Xa:ls the transformer filled the region so full of natural beauty with an ethereal presence, hearkening to the sites still revered all over the world such as Stonehenge.

“While many of the sites Sonny took us to are natural creations, and not the machinations of mankind, the sense respect for the land and awe for its people was hard to deny. The wealth of resources in this area seemed suddenly the gift of the land to the people, and less something to be taken lightly. The only darkness on the wonder filled day of story telling was to hear how much has been lost due to colonization, resource development and a general disregard for the people that have called this area home for thousands of years.

“Their stories make it clear how important the natural world is for people living in this area, and also tell us how dramatically the region has changed since before first contact. It makes the heart heavy to hear Sonny tell about the cultural sites that where destroyed in the name of highways and train-tracks, logging, and more. The tour helped to open eyes to the truth that the very trees are their pyramids of Giza, and with so much of their precious landscapes being altered that connectivity to their ancestral homes has been in very real danger of slipping away. There was, however, a strong sense of hope that tours and sharing with the youth will keep these places sacred so that the spirit of the land can continue to give people a sense of ‘home’ for generations to come.”