By Karen Selesky

Meet the women of the Nineteenth-Century British novel: there’s still time to register for English 333. Come join us in section AB1 on Mondays and Wednesdays from 15:15-17:15.

“It was the best of times, it was the worst of times” . . .

In writing the lived experience of the ordinary Briton, the novelists of this period chronicled and represented the response to rapid change, all the while contributing to the developing forms of the genre.

The nineteenth century marks the rise of the novel as the dominant form of literature in the Western world, and the novelists of Britain were at the forefront of this movement. The century might best be described as one of startling change and progress – economically, socially, politically, religiously – and yet there was great division in how this progress was experienced, between the rich and poor, or the “two nations” as Disraeli characterizes it in his novel Sybil, or the Two Nations (1845). Progress, moreover, was not a singular, upward trajectory but was punctuated by moments of regression, for example, the downturn of the “hungry forties” or the shock to Victorian sensibility brought about by Darwin’s new science and the advent of biblical criticism.

What follows is a series of photographs created by former ENGL 333 student, Sarah Sovereign, with an artist statement describing the connection between novel and image.

Intrigued? Join me to meet these women (and many men) closeup in English 333 this semester.

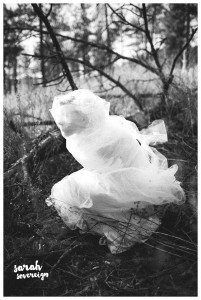

Wilkie Collins’s The Woman in White

Laura Fairlie finds herself as more of a puppet than a person throughout the story. Her character is unable to rise above fretful confidences to her sister and continual pining for Walter Hartright.

My photograph attempts to depict this lack of feminine agency within the novel. A bride, in white, binds her hands in her own dress while ominous, winter-bare trees promise a fruitless marriage. Her downcast eyes suggest submission, her voice is silenced as the shadows engulf her. The dress used is a period wedding dress. The photo is presented in stark black and white to underline the dramatic lack of vitality and the desaturation of life’s riches

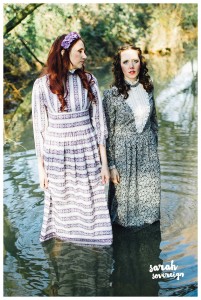

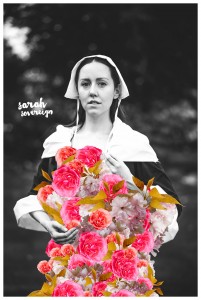

The novel presents two characters who seem to perfectly juxtapose each other, but also reflect a lot of the expectations and projections of the society that surrounds them. We are continually presented with Dinah’s selflessness and Hetty’s narcissism from their introduction. The two photographs I’ve created to reflect this contrast in the two characters is reflected in Dinah’s black and white, plain appearance and the colour, growth and beauty inside her soul. For Hetty’s image, despite her beauty, her inner self only reflects the mirror she often admires herself with. She possesses a truly tragic narcissism. She is cold, antisocial and egotistical and appears to see the world only as a reflection of how the world sees her.

Thomas Hardy’s The Mayor of Casterbridge

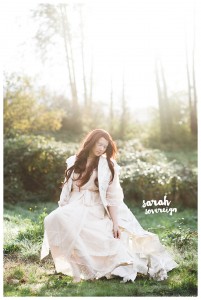

In many ways, the novel is a story about potential – the potential to be great – in a world wrought with flaws and tragic consequence. In the photograph attached, a woman stands wrapped in tulle, poised at the edge of fulfillment. She is a figure of potential, a being whose own story has not yet been told. She is the raw potential of Michael Henchard, not bowed down with alcoholism or pettiness, the even tempered, intelligent visage of Farfrae and the adaptable, swift figure of Elizabeth-Jane. Wrapped as she is, as a cocoon, she is poised to break free. However, can she do so when she is so tightly wrapped? The very same cocoon which fosters her and helps her grow may reveal itself as her prison when she reaches out for freedom. The ideas, beliefs and prejudices we wraparound ourselves can quickly hinder our journey to fulfillment. The figure is crouched, ready to leap up and out but she is so tightly wrapped that she may not be able to reach the form she is meant to and may wither and spoil in her cocoon.

George Gissing’s The Odd Women

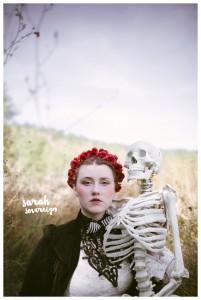

In the photograph, the woman sitting with the skeleton is Isabel. I find her character the most fascinating of all, for all she’s mentioned within the novel. There seems to be such history behind her suicide and “extreme” plainness. As readers we don’t get to know her at all and her death barely registers in the second chapter. What of her melancholia and “brain trouble”? Gissing seems to be suggesting much about the difficulties in being a woman throughout the novel and every female character seems to always be living under the shadow of death. Isabel sits with a skeleton almost in a classic wedding pose, for all her plainness she is unable to marry a man but is able to bond herself to death.

From the beginning, the only achievement open to Isabel seems to be a successful death – there is little for her to rise to, little hope for love (at the very least, very little encouragement for the development of a healthy self-esteem) and her swift placement into poor working conditions quickly means that her health and well-being are only really worth the sum of her paycheque. Is her melancholia genetic mental illness or her own hopeless situation? The suggestion is that ins ome ways, Isabel isn’t successful at being a woman, but she makes an excellent body – a body that can be worked to the bone and discarded in a single sentence.

All Images (and statement) © Sarah Sovereign www.sarahsovereign.com

Elizabeth Ann Makeup Techniques

Models: Jennifer Marie, Dixie Delight, Emily Hamel-Brisson, Sheri Eyre, Pauline Dynowski, Sinead Julia Penner

Some styling by Shiverz Designs (“Goblin Market”, “The Secret Garden”, “Cocoon” and “Skeleton”)

Comments are closed.